Your lawyer for trade mark law

Free initial assessment

Thomas Seifried is a trade mark lawyer with over 20 years of experience in trade mark law and has also been a specialist in intellectual property law since 2007. He has conducted many successful proceedings before courts and trade mark offices.

Contact us

Free initial assessment

Our initial consultation in trademark law is free of charge.

+49 69 9150760

Here you can send us your documents. We will treat your request strictly confidential.

EU and German trademark application

Trademark types, protectability, application strategies - What you need to know about a trademark application

Opposition proceedings before EUIPO and DPMA

What you need to know about opposition procedures before EUIPO and DPMA against the registration of a German trademark or an EU trademark

Declaration of invalidity and cancellation of trademarks at the EUIPO and DPMA

What you need to know about a declaration of invalidity and cancellation of a trademark at the EUIPO and DPMA

What is a trade mark infringement?

Summary

Trademark infringement is the use of a sign that resembles or is similar to a trademark (‘sign similarity’) for the same or similar products for which the trademark is registered (‘product similarity’). In the case of well-known trademarks, product similarity is not a prerequisite for trade mark infringement.

![[Translate to English:] Markenrechtsverletzung Markenparodie](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/b/csm_PUDEL_ad8f2d2ad2.png)

In principle, the more similar the sign used is to the protected trademark and the more similar the goods or services (products) for which the sign is used and the products for which the trademark is registered are, the more likely the trademark infringement is. The distinctive character of the trademark must also be taken into account and whether the sign has been ‘used as a trade mark’ at all.

Infringing uses

Which acts of use can trigger a trade mark infringement?

A trade mark proprietor may have the use of identical or similar signs for identical or similar products (goods or services) prohibited by a court if there is at least a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public as a result of the use. The law lists examples of potentially infringing uses in § 14 III and IV MarkenG and Art. 9 III and IV UMV. The most important ones are offering and marketing. However, even the use of a sign identical with or similar to a trade mark in advertising may constitute a trade mark infringement (§ 14 III No. 6 or Art. 9 III e) UMV). Accordingly, the use of a trademark-protected designation for a lottery can already infringe a trademark.

Example:

The application of a beverage manufacturer for a raffle with the designation

"MKG - Mega-Kasten-Gewinnspiel" (Mega Crate Raffle)

was an infringement of the trade mark "MKG", registered for advertising and catering for guests (BGH, decision of 14 October 2010 - I ZR 212/08 - Mega-Kasten-Gewinnspiel).

No trademark infringement: The permitted naming of third-party trademarks in product descriptions

Trademark use for product description

By no means every use of another person's trademark is also a trademark infringement. The use of a trademark (i.e. trademark-like or trademark-identical terms) is permitted under § 23 MarkenG or Art. 14 EUTMR, for example, for the necessary product description.

Example BGH judgment of 22.1.2009 - I ZR 139/07 - PCB:

The naming of "pcb" as a common abbreviation for "printed circuit board" is not an infringement of the trademark "PCB-POOL" .

The same applies to customary descriptive statements or in permissible comparative advertising (i.e. if there is no trademark infringement, BGH, judgment of February 4, 2010, I ZR 51/08, para. 41 - Powerball). Trademarks may also be mentioned if this is necessary to describe spare parts. Prerequisite: Such use is not contrary to honest practices in industrial and commercial matters (ECJ, judgment of 11.9.2007, C-17/06, para. 34 - Céline).

Examples:

- The labeling of a food supplement with the name "Enzymix" infringes the food supplement trademark "Enzymax" because the reference to a mixture of enzymes would not be described as "Enzymix" but as ""Enzym-Mix" (OLG Köln judgment of 25.9.2009 - 6 U 68/09 - Enzymax/Enzymix).

- The use of the designation "H 15" for a prescription drug is not a trademark infringement. This is because the relevant target public (health professionals and pharmaceutical distributors) sees this as a reference to Boswellia serrata frankincense extract (OLG Stuttgart judgment of 10.6.2010 - 2 U 87/09 - H 15).

Use of third-party trademarks to describe a compatibility or as a spare part

Third-party trademarks are often used to indicate the suitability of a product as a spare part or compatible product. According to Section 23 I No. 3 MarkenG and Art. 14 I c) EUTMR, such use is only permitted under the following conditions:

The named trademark must be unambiguously recognizable as a third-party trademark. It is not permitted to give the impression that the trade mark of the compatible products is one's own trade mark (OLG Frankfurt judgment o. 03.11.2016 - 6 U 63/16 - Lube-Shuttle). Compatibility must necessarily require the naming of the trademark (see ECJ, GRUR 2005, 509 para. 35 - Gillette). If, for example, there are technical standards or norms that describe compatibility, the trademark may not be named (see ECJ, GRUR Int 1999, 438 para. 60 - BMW/Deenik; BGH, GRUR 2011, 1135 para. 20 - GROSSE INSPEKTION FÜR ALLE). The trademark must be used sparingly. Any advertising effect that goes beyond the necessary brand mention must be avoided. A prohibited promotional use would be, for example, the inclusion of the trademark in the browser title (i.e. use in the "title tag") of a website or in the domain (see BGH, judgment of 28.6.2018 - I ZR 236/16 - keine-vorwerk-vertretung). It would also be prohibited to use the figurative mark instead of describing the mark with words (see BGH of 14.4.2011 - I ZR 33/10 - GROSSE INSPEKTION FÜR ALLE).

Permitted trademark use in advertising after "exhaustion"

Another case in which the trademark owner cannot prohibit the resale of goods bearing the trademark or the advertising of these goods is the principle of exhaustion under trademark law.

"Use as a trademark"

Prerequisite for a trade mark infringement

The first prerequisite for a trade mark infringement is always the "use as a trade mark" of the respective sign: The potentially trade mark infringing sign must also be perceived as an "indication of origin", i.e. as a trade mark. This is often doubtful, for example, if this sign is regarded as a product design or model designation.

Is the sign perceived as a trade mark at all?

The main function of a trade mark is to identify the origin of a product from a particular business. The European General Court also regularly emphasises this "origin function" of the trade mark (e.g. GC, Judg. of 8 JUNE 2017 - C-689/15 - W. F. Gözze Frottierweberei GmbH, Wolfgang Gözze v. Verein Bremer Baumwollbörse). The viewer of a print affixed to clothing must therefore see it as an indication of the origin of the clothing from a particular undertaking and not merely as a decorative element. In other words, a designation must also be perceived as a trade mark in order for there to be any trade mark infringement at all. This is the so-called "use as a trade mark". If a sign or designation is not perceived as a trade mark, but only as a product decoration, for example, there is no use as a trade mark and thus no trade mark infringement.

The Federal Supreme Court therefore denied a trademark infringement in the "CCCP" case: "CCCP" was the abbreviation for "USSR" in Cyrillic characters. The BGH assumed that the inscription "CCCP" affixed to the front of T-shirts was to be understood as a symbol of the former Eastern Bloc states and was to be regarded exclusively as a decorative element and not, for example, as an indication of the origin of a particular company. Therefore, the defendant did not infringe the trade mark "CCCP" because "CCCP" was not used as a trade mark at all, but as a decoration (BGH, judgement of 14.01.2010 - I ZR 82/08 - CCCP).

The European General Court also clarifies that the mere affixing of an EU trade mark to towels as a quality mark ("cotton flower") is not to be regarded as use as a trade mark (GC, judgement of. 8 June 2017 - C-689/15, para. 51 - W. F. Gözze Frottierweberei GmbH, Wolfgang Gözze v Verein Bremer Baumwollbörse).

Both for the application procedure and in the case of infringement, the following applies: The more original and "artificial" a designation is, i.e. the less it describes the product in question and its respective field of application, the more likely it is to be registrable as a trade mark and the stronger it is also in the subsequent infringement proceedings.

Examples of "use as a trademark" from case law

Trademark or design?

Anyone who wants to use their trademark to take action against a trademark infringement must jump over an important hurdle: "trademark use." This is a prerequisite for any trademark infringement. This is particularly doubtful in the case of the use of a sign as a decorative element or as a model name.

Example BGH, decision of 14 January 2010 - I ZR 82/08 – CCCP

Is the "CCCP" imprint on the T-shirt considered a trademark or design? The plaintiff was a licensee of the action word mark "CCCP" and sold logo shirts with the imprint "CCCP". The trademark was registered for, among other things, "T-shirts." The defendant sold the pictured logo shirt with the sign "CCCP" in its online store.

Example BGH, decision of 24 November 2011 - I ZR 175/09 - Medusa (Versace)

Another ruling deals with the use of a sign similar to Versace's "Medusa" marks on a tabletop. The question here was also: Is the sign considered a trademark, i.e., an indication of the table's origin from a particular company, or simply a decoration?

The plaintiff, Gianni Versace S.p.A., is the owner of the internationally registered figurative mark No. 626654 registered for "meubles".

The defendant sold marble mosaics on the Internet, including the motif shown.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant infringed the rights to its figurative mark by selling the mosaics with the images of Medusa. The defendant, on the other hand, claimed that the figure of the Medusa by Phidias from the Rondanini collection exhibited in the Glyptothek in Munich had served as the model for the mosaics it distributed. Here, too, the BGH denied trademark use and trademark infringement. This is because the image motifs of the Medusa are only seen as the decoration of the goods. The motif has an exclusively decorative character and is not regarded as an indication of origin from a specific company.

Here, too, the Bundesgerichtshof denied trademark use and trademark infringement. This is because the image motifs of the Medusa are only seen as the decoration of the goods. The motif has an exclusively decorative character and is not regarded as an indication of origin from a specific company.

Trademark use in the case of well-known trademarks

Well-known trademarks have a broader scope of protection. Use as a trademark is also required for the infringement of trademarks with a reputation. However, according to the case law of the ECJ, it is sufficient for the infringement of a trademark with a reputation (Art. 5 II MRRL, Sec. 14 II No. 3 MarkenG) that the collision sign is perceived as an ornament, but that it is mentally linked to the trademark with a reputation due to the high degree of similarity (BGH, judgment of February 3, 2005 - I ZR 159/02 - Lila-Postkarte; GC of October 23, 2003 - C-408/01 - Adidas/Fitnessworld).

Use as a trademark of colour marks

The use of a colour in advertising or on goods or their packaging will only exceptionally be construed as a trade mark. In an infringement case brought by the Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe against Santander, the BGH pointed out various shoals: On the one hand, an infringement of Santander's red colour mark depends on whether Santander is "using the colour in a trademark-like manner": the red colour shade would therefore also have to be regarded as an "indication of origin", i.e. it must be regarded as a trademark and not merely as an ornament. The Federal Court of Justice considers use as a trade mark to be conceivable if the retail banking public is used to colours being regarded as indications of origin in isolation (i.e. independently of, for example, a word element "Santander") (Federal Court of Justice, Judgment of 23.9.2015 - I ZR 78/14, para. 94 - Sparkassen Rot/Santander Rot).

However, there are exceptions: For example, the distribution of language learning software in yellow packaging infringed the German colour mark 39612858 "Gelb" for bilingual dictionaries of the Langenscheidt publisher, which was registered by virtue of passing off. The BGH assumed use as a trade mark: On the domestic market of bilingual dictionaries, colours would prevail over the labelling habits. This would radiate to the market of neighbouring products, which included language learning software. Therefore, the colour "yellow" used in this product area would also be understood as a product mark, i.e. as use as a trade mark (BGH, judgment of 18 September 2014 - I ZR 228/12 - Gelbe Wörterbücher).

Descriptive terms in advertising as trademark use?

The use of names or words that are perceived as a description of a product is also not a trademark infringement. This is particularly true in advertising.

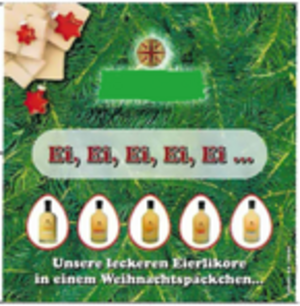

The case: A manufacturer of egg liqueur advertised five different types of egg liqueur with the illustrated advertisement. Another traditional egg liqueur manufacturer took exception to this. He was the owner of the trademark "Eieiei", registered for spirits. It sent the eggnog producer a warning letter for trademark infringement and demanded that it submit a cease-and-desist declaration with a penalty clause. The egg liqueur manufacturer did so, but did not pay the warning costs that were also demanded. The traditional egg liqueur manufacturer attempted to claim the warning costs in an action before the Düsseldorf Regional Court.

The Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court dismissed the claim. It rejected a claim for reimbursement of warning costs because there was no trademark infringement. The advertising for an egg liqueur with the words "egg, egg, egg, egg, egg" did not infringe the "Eieiei" trademark. The Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court confirmed the decision: The term "Ei, Ei, Ei, Ei, Ei" had not been used to indicate origin: A use indicating origin and thus a use as a trademark was remote. The challenged advertising text "egg, egg, egg, egg, egg" would only describe the product. Eggs are the core ingredient of egg liqueur. The use of descriptive information could not, in principle, constitute trade mark use. The public reading the advertisement would easily recognize that "egg, egg, egg, egg, egg" is a mere factual statement. The fivefold repetition does not change this. In advertising, repetition is a rhetorical stylistic device that has long been known in advertising psychology. The embedding in the advertising also speaks for a mere promotional and non-trademark use: all five liqueurs depicted contain the ingredient "egg". Finally, the name of the own company was also prominently reproduced (made unrecognizable with green color in the above illustration). This also argues against trademark use of "Ei, Ei, Ei, Ei, Ei" (OLG Düsseldorf of 27.04.2023 - 20 U 41/22 - Ei, Ei, Ei, Ei, Ei, Ei).

Trademark use of pharmaceutical trademarks

The registration of a medicinal product under its trademark in the ‘Lauer-Taxe’ already constitutes trademark use, at least as long as it is not labelled ‘out of stock’ (OLG Köln, judgment of 25 July 2014 - 6 U 197/13 - Trademark use (L-Thyrox)).

Trade mark infringements through model designation

![[Translate to English:] Markenrechtsverletzung markenmäßige Benutzung Modellbezeichnung SAM](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/f/csm_BGH_SAM_22c5b9499a.png)

The BGH was unable to recognise any infringement of the ‘SAM’ trademark in this case. It established the following principles in the ‘SAM’ decision:

The better known the trademark is, the more likely it is to be assumed that it has been infringed. If the model name itself is well-known (e.g. the ‘501’ from Levi's), the specific way in which the model name is used may indicate that the public perceives it as a trademark. In the case of particularly frequently occurring first names, however, it is conceivable that they will only be regarded as a model designation and not as an indication of origin.

If the model name is not known, it can still be assumed to be a trademark if it is used in ‘direct connection’ with the manufacturer's or umbrella brand. On the other hand, the use of a model name that is not known as a trademark in an inconspicuous place in the description of the offer will usually not be regarded as trade mark use. Such cases - as in the ‘SAM’ case’ - are therefore usually not trade mark infringements. Accordingly, the Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt, to which the Federal Court of Justice had referred the case back, subsequently rejected an infringement of the trademark ‘SAM’ by stating it only in the item description (Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt of 1 October 2019 - 6 U 111/16 - No trademark use of a first name as a model name for clothing).

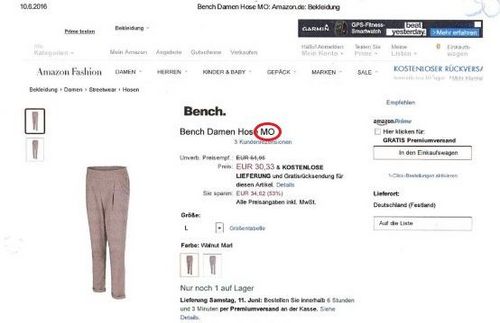

BGH, judgement of 11 April 2019 - I ZR 108/18 - MO

The facts of the ‘MO’ judgement were typical of a trademark infringement by a model name. The case concerned the following Amazon offer:

It also concerned the following description on a sales invoice

‘Bench ladies’ trousers MO Large walnut marl B005FPJ0AG’.

The BGH considers it possible in principle that a well-known umbrella brand or model name is understood as an indication of origin and therefore the use of a protected (or similar) name as a model name is a trade mark infringement. It cites the well-known ‘501’ from Levi's as an example. In the ‘MO’ case, however, the BGH lacks findings on the reputation of ‘MO’. The BGH points out that the public usually sees the indication of origin in the preceding manufacturer's name (in the ‘Bench’ case). The grounds for the judgement conclude with the words:

‘In the case of such strings of signs which also contain letters and numbers, there may be much to suggest that the public sees the indication of origin in the preceding manufacturer's designation alone.’

According to the BGH, in cases such as these, the manufacturer's mark alone is usually regarded as a trademark, but not the model designation, be it ‘SAM’ or ‘MO’. An exception applies if the model designation is known.

However, the Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt, to which the case was referred back, subsequently considered the Amazon offer to be a trade mark infringement again. In this case, ‘MO’ was not just a model name, but would rather be regarded as a secondary trade mark: ‘MO would be used here “in direct connection with the manufacturer or umbrella brand” and in a “prominent position”. The insertion ‘ladies’ trousers’ would also only make it clear “that two independent signs are involved, namely an umbrella trade mark and a secondary trade mark specifically for the specific item of clothing”.

The Higher Regional Court of Hamburg took a different view in a comparable case (see below).

The description on the sales invoice

‘Bench ladies’ trousers MO Large walnut marl B005FPJ0AG’.

was no longer considered by the OLG Frankfurt to be a trade mark infringement. ‘MO’ was ‘fully integrated into the sign combination’. Here again, the empirical principle established in the ‘MO’ decision of the Federal Court of Justice ‘that the public sees the indication of origin solely in the preceding manufacturer's indication’ applies (OLG Frankfurt of 13 August 2020 - 6 U 94/17 - Trademark use of a clothing brand - MO).

Recommendation for the use of model designations

If you want more certainty when using model designations, you should definitely carry out a trade mark search before using a model designation.

Read here: How to carry out a trade mark search.

In the relevant offers, the model name should then be used in the following order:

[manufacturer name/trademark] [item descriptions, e.g. ‘ladies’ trousers"] [model name]

It is important that the model name is not emphasised over the trademark, for example by using capital letters.

Likelihood of confusion according to settled case-law

The comparison of the signs at issue

The global assessment of the likelihood of confusion must, so far as concerns the visual, phonetic or conceptual similarity of the signs at issue, be based on the overall impression given by the signs, bearing in mind, in particular, their distinctive and dominant elements. The perception of the marks by the average consumer of the goods or services in question plays a decisive role in the global assessment of that likelihood of confusion. In this regard, the average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details (see ECJ judgment of 12 June 2007, OHIM v Shaker, C‑334/05 P, EU:C:2007:333, paragraph 35 and the case-law cited).

The distinctive and dominant elements of the marks in question

According to the case-law, for the purpose of assessing the distinctive character of an element of a mark, an assessment must be made of the greater or lesser capacity of that element to identify the goods for which the mark was registered as coming from a particular undertaking, and thus to distinguish those goods from those of other undertakings. In making that assessment, it is necessary to take into account, in particular, the inherent characteristics of that element and to ask whether it is at all descriptive of the goods for which the mark has been registered (see ECJ judgment of 3 September 2010, Companhia Muller de Bebidas v OHIM – Missiato Industria e Comercio (61 A NOSSA ALEGRIA).

The likelihood of confusion in the narrower sense

According to settled case-law, a global assessment of the likelihood of confusion implies some interdependence between the factors taken into account and, in particular, between

- the similarity of the trade marks and

- that of the goods or services covered.

Accordingly, a lesser degree of similarity between those goods or services may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the marks, and vice versa (ECJ judgments of 29 September 1998, Canon, C‑39/97, EU:C:1998:442, paragraph 17, and ECJ of 14 December 2006, Mast-Jägermeister v OHIM – Licorera Zacapaneca (VENADO with frame and others).

The role of distinctiveness in trademark infringement

A high degree of distinctiveness increases the scope of protection of a trade mark and makes a likelihood of confusion more likely. The more original and individual a name is for the product in question, the ‘stronger’ the trade mark is. The distinctiveness of a trade mark can increase if the trade mark becomes better known, for example through intensive advertising. The trade mark then becomes ‘stronger’, so to speak. A descriptive name, which in itself would be unprotectable, can therefore still be registered as a trade mark if it has acquired ‘reputation’ (see below). Similarly, a weak or averagely distinctive trade mark may have strengthened its distinctiveness through advertising.

Registered trade marks have at least weak inherent distinctiveness

A registered trade mark is considered to have at least weak inherent distinctiveness (BGH of 2 April 2009 - I ZR 209/06 - POST/RegioPost). Registered trade marks are therefore deemed to be capable of protection. The objection in trade mark infringement proceedings that the registered trade mark is not distinctive at all and therefore not eligible for protection is therefore unsuitable.

Similarity of the signs: visual, phonetic or conceptual similarity of the signs

Likelihood of confusion of the signs means,

- visual,

- phonetic or

- conceptual similarity

Similarity in only one of these categories may be sufficient for a likelihood of confusion (Euopean General Court, judgment of 22 June 1999, C-342/97 - Lloyd/Klijsen, para. 28). A visual or phonetic similarity of a sign can in turn be neutralised by a clear meaning of a sign (BGH of 29.7.2009 - I ZR 102/07 - AIDA/AIDU).

Visual similarity

Example: No likelihood of confusion due to (written) visual similarity: The word/figurative mark ‘PUMA’

is not infringed by the use of the figurative sign ‘PUDEL’ (BGH, judgement of 2 April 2015 - I ZR 59/13 - Springender Pudel).

BUT: The use of the figurative sign ‘PUDEL’ nevertheless infringes the well-known(!) trademark ‘PUMA’, because the likelihood of confusion is irrelevant in the case of well-known trademarks (see above) and the reputation of the well-known trademark is exploited here (BGH, judgement of 2 April 2015 - I ZR 59/13 - Springender Pudel).

Another example: There is no likelihood of confusion between the trademarks Vivendi and VIVANDA, mainly due to the different vowels (BPatG of 14 November 2012, 26 W (pat) 503/11 - Vivendi/VIVANDA).

Likelihood of confusion due to phonetic similarity

- Characters made up of the same letters usually create a similar overall impression. The signs "IPS" and "ISP" are therefore phonetically similar (BGH v. 5.3.2015 - I ZR 161/13 - IPS/ISP).

- Because a possibly unclear pronunciation must also be taken into account, "combit" and "Commit" are phonetically similar. "Commit" are phonetically similar (BGH v. 12.7.2018 - I ZR 74/17 - combit/Commit).

Examples: No phonetic similarity

- Mainly because of the different vowels there is no likelihood of confusion between the trade marks "Vivendi" and "VIVANDA" (BPatG v. 14.11.2012 - 26 W (pat) 503/11 - Vivendi/VIVANDA ).

- Because of the two consonants "n", there is no likelihood of confusion between "Anson's" and "ASOS" (OLG Hamburg v. 11.12.2014 - 3 U 108/12 - Anson's/ASOS).

Neutralisation of sound similarity by the figurative elements?

The Federal Court of Justice (BGH) only assumes a neutralisation of phonetic similarity or phonetic identity by the figurative elements of the opposing sign if the goods concerned are only(!) bought "on sight" and not also on demand (BGH, judgement of 20.01.2011 ref. I ZR 31/09 - Kappa). This will rarely ever be the case. The European General Court seems to rather assume such a neutralisation here, namely already if the goods are usually also visually perceptible at the time of purchase (European General Court, judgment of 13 September 2007 - C-234/06 P - Muelhens GmbH & Co. KG v OHIM).

Example:

The Beck brewery had a registered figurative mark for beer from 1993 to 1999, in which an upside-down key was depicted:

This trade mark infringed the earlier word and figurative mark "Original Schlüssel Obergärige Handwerkliche Hausbrauerei" of Brauerei Schlüssel. This trade mark was also registered for beer. The signs had the same meaning. The trade mark of Brauerei Beck was therefore cancelled again (BGH, decision of 18.03.1999 - I ZB 24/96 - Schlüssel).

Product similarity - Which goods or services are opposed to each other?

Whether there is product similarity must be examined on the basis of several factors: The nature of the goods, their intended purpose and use, whether the products compete with each other (substitutability) or complement each other (European General Court of 18.12.2008, C-16/06 - Éditions Albert René, para. 65) or whether they are marketed together (Bundesgerichtshof, decision of 30 March 2006, I ZR 96/03 - TOSCA BLU, para. 13).

Example:"Wholesale and retail services for clothing" (meaning the selection of the product range) and clothing itself are similar (BGH judgement of 31 October 2013 - I ZR 49/12 - OTTO CAP).

Infringements of Well-known trademarks

Infringement of trademarks well known in Germany or well known in the European Union

No likelihood of confusion required for infringement of well-known trademarks!

No likelihood of confusion is required for the infringement of a trademark with a reputation (European General Court v. 23.10.2003 - C-408/01 Adidas-Salomon u. Adidas Benelux/Fitnessworld Trading Ltd). For the infringement of a well-known trademark, the origin function of the well-known trademark does not have to be infringed. However, the attacked sign must be at least similar to the well-known mark (so-called "similarity of signs", cf. BGH v. 26.11.2020 - I ZB 6/20 - RETROLYMPICS; BGH v. 28.06.2018 - I ZR 236/16 - keine-Vorwerk-Vertretung.de). A well-known trademark is already infringed if

- one assumes economic or organizational connections to the trademark owner due to the use of the sign or

- this use of the sign is detrimental to the distinctive character of the mark with a reputation (European General Court, judgment of 23.10.2003 - C-408/01 - Adidas-Salomon/Fitnessworld, para. 27) for those goods or services for which the mark is registered (BGH v. 11.4.2013 - I ZR 214/11, para. 60 - VOLKSWAGEN)

Distinctiveness is particularly exploited when someone, by using a sign similar to a mark with a reputation, attempts to take advantage of the "pull" of the mark with a reputation in order to benefit from its power of attraction without any financial consideration and without making any effort of his own (see European General Court, GRUR 2009, 756 para. 49 - L'Oréal/Bellure; BGH v. 31.10.2013 - I ZR 49/12 - OTTO CAP). It is sufficient that there is a risk that an average consumer for the registered goods of the mark with a reputation could behave differently because of the use of the identical or similar sign (European General Court - L'Oréal/Bellure loc. cit.; BGH - VOLKSWAGEN, loc. cit., para. 61). An infringement of the well-known German trademark 1067586 - "OSCAR"- is in any case not excluded because the use of the term "Oscar" is associated with the annual awarding of the "Oscar statuette" in the USA (BGH v. March 8, 2012 - I ZR 75/10, para. 41 - OSCAR).

Examples of well-known trademarks under Sec. 14 (2) No. 3 German Trademark Act (MarkenG) or Art. 9 (2) c) EUTMR:

- The German word mark 2001632 "PUMA", see above (BGH, judgment of April 2, 2015 - I ZR 59/13 - Springender Pudel).

- The German word mark 1019711 "VORWERK" (see BGH, judgment of June 28, 2018 - I ZR 236/16 - keine-Vorwerk-Vertretung.de).

- The German word mark No. 30126772 "Otto" (BGH, judgment of Oct. 31, 2013 - I ZR 49/12 - OTTO CAP)

- The German word mark 1067586 - "OSCAR" (BGH, judgment of March 8, 2012 - I ZR 75/10, para. 41 - OSCAR)

- The European Union word mark "VOLKSWAGEN" 703702 (BGH, judgment of April 11, 2013 - I ZR 214/11 - VOLKSWAGEN/Volks.Inspektion)

- The German word mark 1080850 "Swirl" (BGH, , judgment of April 2, 2015 - I ZR 167/13 - Staubsaugerbeutel im Internet)

- "Fisherman's Friend" (LG Frankfurt a.M. of 28. 4. 2000 - 3/12 O 13/00 - FISHERMAN'S FRIEND)

Example: Infringement of the well-known trademark ‘Volkswagen’

The advertising for a ‘VolksInspektion’ infringes the well-known European trade mark 703702 ‘Volkswagen’. BGH: Trademark infringement in the form of a ‘likelihood of confusion in the broader sense’ is possible here if the public assumes economic and organisational links between the parties or if the distinctive character of the well-known trademark is impaired (BGH of 11.04.2013 - I ZR 214/11 - Volkswagen).

Example of infringement of a well-known German trademark: BGH of 31 October 2013 - I ZR 49/12 - OTTO CAP

The sale of baseball caps with a sewn-in label ‘OTTO’ infringes the well-known trademark ‘OTTO’ (German word mark 30126772, registered inter alia for ‘wholesale and retail services for clothing’). It is sufficient to assume that the goods and services come from the same company. Large retailers would also offer their own brands.

Likelelihood of confusion with single letter trademarks

![[Translate to English:] Markenrechtsverletzung Einzelbuchstaben Bogner](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/d/csm_Bogner_B_b5d27b9a07.jpg)

Single-letter trademarks have a narrow scope of protection. This is because figurative differences play a greater role here. Figurative similarities are more likely to be denied here than with signs consisting of several letters. In terms of sound, single-letter marks are not pronounced with the letter, but usually with the trademark behind it. For this reason, single-letter trademarks have a narrow scope of protection. There is therefore usually not sufficient phonetic similarity for a trade mark infringement in the case of single letter trade marks. In the past, the Federal Court of Justice (BGH) has ruled that there is no infringement of the trademark

Trade mark infringement in the case of signs with several elements ("combination signs)

Trademarks are often composed of several elements. These can be, for example, several words, words and graphic elements, several graphic elements, several elements of an overall design (e.g. back pocket and ‘Red Tab’ by Levi's, see BGH of 5 November 2008, I ZR 39/06 - Stofffähnchen I) or a combination of these. A typical example are word/figurative marks. Trademarks with several elements are often juxtaposed with signs that themselves consist of several elements.

Overall impression also counts for combination marks

Whether such a combination sign can be confused with a trademark or a combination mark is also assessed on the basis of the overall impression (see the European General Court of 12 June 2007 - C 334/05 P - Limoncello; BGH of 26 October 2006 - I ZR 37/04 - Goldhase; BpatG of 25 January 2011, 27 W 533/10 - ROCCO MILES).

Predominant (dominating) sign elements

If sign components of the potentially infringing sign are dominant, there is a likelihood of confusion between the two overall designations if the respective dominant component is identical (BGH, 22 July 2004 - I ZR 204/01 - Mustang). What cannot be protected cannot be distinctive. However, a descriptive element of a trademark that is not protectable in itself cannot have a formative influence on the overall impression of a trademark, because otherwise trademark protection could be obtained for descriptive information (BGH of 27 March 2013, I ZR 100/11 - AMARULA/Marulablu, para. 59).

Non-dominant, but ‘independently characterising’ components (exception)

An element of a sign can also have an ‘independent distinctive character’. As a rule, however, the principle that the overall impression of the opposing signs is decisive in the case of a trade mark infringement applies.

Example BGH of 3 April 2008 - I ZB 61/07 - SIERRA ANTIGUO, para. 34:

The trademark ‘SIERRA ANTIGUO’ is not infringed by ‘1800 ANTIGUO’. This is because only the element ‘ANTIGUO’ was taken from it. Otherwise, trademark law would inadmissibly assume element protection instead of the overall impression (BGH of 3 April 2008, I ZB 61/07 - SIERRA ANTIGUO, para. 34).

Special circumstances (e.g. the reputation of a company sign) must therefore be present for an independently distinctive position of sign elements. Otherwise, the rule that the signs in question must be compared as a whole when examining the likelihood of confusion would become an exception (BGH, judgement of 5 December 2012 - I ZR 85/11 - Culinaria/Villa Culinaria, para. 50).

Example ECJ of 6 October 2005 - C-120/04 - THOMSON LIFE:

The use of the sign ‘THOMSON LIFE’ infringes - in the case of product identity - the trademark ‘LIFE’ because the sign element ‘THOMSON’ is recognisably a well-known company sign (company). ‘LIFE’ in ‘THOMSON LIFE’ was therefore an independently distinctive element of the sign. Non-defining but ‘independently distinctive’ elements are exceptions.

Trade mark infringement through preparatory acts - labels, packaging and other means of labelling

According to Art. 10 EUTMR and Section 14 (4) German Trademark Act (MarkenG), a trademark owner can also explicitly prohibit the affixing of labels as well as the offering or possession of labels that are intended to prepare a trademark infringement.

Interim right of the proprietor of a later trademark in infringement proceedings under Art. 16 of the EU Trademark Regulation and § 22 German Trademark Act (MarkenG)

Defence in the event of a trademark infringement against the trademark owner

In some cases, the attacked trademark infringer is also the owner of a trademark. Anyone who is attacked for infringing an EU trademark or German registered trademark and is themselves the owner of a corresponding (possibly infringing) later trademark (EU trademark or national trademark) should be able to defend themselves against a trademark infringement. This applies to cases in which the EU trademark being sued is itself tainted with a defect (lack of distinctive character, non-use). Art 13a EUTMR is complicated and concerns various case constellations. There is a comparable regulation for German trademarks in Section 22 MarkenG.

Anyone who has used their own later trademark and is therefore claimed against by the owner of an identical or similar earlier EU trademark or German registered trademark does not infringe the earlier trademark if the later trademark could not be declared invalid. Art. 16 EUTMR and § 22 MarkenG are defences in infringement proceedings. These defences essentially concern cases in which the proprietor cannot enforce its earlier EU trademark because

the earlier trade mark has lost its distinctive character and therefore does not conflict with the later trade mark;

the proprietor of the earlier trade mark has tolerated the use of the later trade mark (EU trademark or national trade mark) for five years, or

the proprietor cannot prove the use of his own earlier trade mark after the expiry of the five-year grace period;

the earlier trademark was not actually eligible for protection at the time of application or priority because there was an absolute ground for refusal (e.g. lack of distinctive character or a descriptive indication) and only became eligible for protection after the application for the later national trademark as a result of market penetration.

According to Art. 16 (3) EUTMR and Section 22 (2) German Trademark Act, the owner of the later trademark cannot oppose the use of the earlier trademark in infringement proceedings.

Trade mark infringement through trade mark application

According to established German case law, the filing of a trademark application already creates a risk of first infringement for an infringing use in relation to the goods and services applied for (BGH of 22 January 2014 - I ZR 71/12 - REAL-Chips). The risk of first infringement is eliminated by an ‘actus contrarius’. In the case of a likelihood of first infringement of a trademark caused by a trademark application, only a renunciation of the trademark will therefore eliminate the likelihood of first infringement (BGH of 23 September 2015 - I ZR 78/14, para. 56 - Sparkassen-Rot/Santander-Rot). The application for a trademark that collides with a third-party trademark can therefore not only result in (comparatively favourable) opposition proceedings before the trademark office. Such a trade mark application can already lead to court proceedings for trade mark infringement, for example in proceedings for an interim injunction.

Trade mark infringement through offers of original goods

Trademark infringement does not only apply to offers of counterfeit goods. Offering original goods can also be a trade mark infringement if the goods were placed on the market without the trade mark owner's consent. As the principle of Europe-wide exhaustion applies in trade mark law, it is, for example, an infringement of trade mark rights if goods of a US trade mark owner are offered in Europe without the owner's consent.

Trademark infringement due to repackaging and removal of mandatory legal information

If goods that are only sold in packaging by the trademark manufacturer are offered unpackaged, e.g. on eBay, this may constitute a trademark infringement if it damages the image of the trademark (GC of 12 July 2011 - C-324/09 - L'Oreal SA and others v eBay International AG and others). A trade mark infringement is also assumed if the packaging contains legally required information about the identity of the manufacturer, the intended use and the composition. This is the case, for example, with cosmetic products. If such items are offered without packaging, the quality function of the goods is impaired (GC of 12 July 2011 - C-324/09 - L'Oreal SA and others / eBay International AG and others). Exceptions apply to medicinal products and medical devices if there is a risk of foreclosure of the national markets within Europe as a result of the legal action (CG of 26 April 2007 - C-348/04 - Boehringer Ingelheim/Swingward).

Trade mark infringements on the Amazon marketplace - ‘attaching’ to third-party offers

OLG Frankfurt of 27. October 2011 - 6 U 179/10: The subsequent insertion of one's own trade mark can be abusive of rights

Sometimes a provider changes a product page by inserting his own trademark himself. In a case decided by the Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt (judgment of 27.10.2011 - 6 U 179/10), such a provider had subsequently sued a competitor for infringement of its trade mark. Wrongly, according to the Higher Regional Court: There was indeed a trademark infringement per se, because the injunctive relief was not based on fault. However, such an action was an abuse of rights. This provider had deliberately allowed its competitor to fall into the trap. The special feature of the case: For more than 1 1/2 years, both suppliers had sold the same glasses side by side under this product page. If he now added his own brand to the offer, he would at least have to inform his competitors of this, said the Frankfurt Higher Regional Court.

LG Frankfurt of 11 May 2011, Ref. 3-08 O 140/10: Subsequent insertion of one's own trademark can even be anti-competitive

The Regional Court of Frankfurt took an even stricter view in a judgement of 11 May 2011 (Ref. 3-08 O 140/10). The parties to the aforementioned proceedings before the Higher Regional Court of Hamm disputed in Frankfurt whether it was not itself anti-competitive for a party to subsequently insert its trademark into the product page in order to subsequently take action against competitors for infringement of this trademark. The Frankfurt Regional Court had assumed exactly this: If the product page had remained unchanged for five months, one could not suddenly insert a trade mark and use it to take action against competitors under trade mark law. That would be an anti-competitive targeted obstruction.

The decision cannot be generalised without further ado. After all, an Amazon seller must regularly check the product pages. The Higher Regional Court of Hamm assumes that an Amazon trader may not let his product pages out of his sight for longer than three days. The Amazon terms and conditions themselves even stipulate a daily obligation to check.

Is attaching an EAN number to an already existing EAN number anti-competitive?

In a case before the Regional Court of Bochum (judgement of 3.11.2011 - Ref. 14 O 151/11), the question was whether such appending is not itself anti-competitive. The Bochum Regional Court denied misleading information about the supplier: potential buyers would not associate the EAN number with a specific supplier, but rather with a specific product.

Amazon Marketplace traders are also liable for the infringement of a trade mark that was only added to the offer page afterwards

BGH of 3 March 2016 - I ZR 140/14 - Offer manipulation at Amazon

he case: The defendant operated a retailer shop on the Amazon Marketplace. He posted a "finger mouse" for notebooks. Originally, the listing page for this product probably contained the manufacturer's name of the finger mouse, namely "Oramics". Later, the page was changed. Now the offer read:

"Trifoo [...] Finger Mouse [...]".

The plaintiff became the proprietor of the trade mark "TRIFOO" after the offer was made for the first time. She claimed infringement of her trade mark. In any case, the defendant would be liable as a "disturber". The argument was that posting on Amazon was "risk-increasing behaviour". Anyone who offered products on Amazon Marketplace had to constantly expect that their rights would be infringed. This is because they must constantly expect that the offer page will be changed. As a consequence, a marketplace trader must regularly check his offer. If he did not do so, he would be liable for infringements at least as a "Stoerer" (interferer).

The Federal Court of Justice upheld the plaintiff's claim: as is well known, anyone who offers goods on the Marketplace must constantly expect that the offer page will be changed and that he will infringe the rights of others as a result. The consequence: According to the BGH, a Marketplace trader must

"regularly check an offer posted on Amazon Marketplace [...] to see whether infringing changes have been made".

If he fails to do so, he is liable for infringements.

BGH on the beginning and scope of an Amazon trader's duty to check

Unlike service providers (§§ 8 to 10 TMG) who do not have a general duty to check, the duty of a Marketplace trader to check does not begin only after the indication of an infringement but already with the setting of the offer. The Federal Court of Justice (BGH) also commented on the intervals of the inspection: anyone who leaves his offer unobserved for a fortnight is in any case in breach of his duty to inspect (BGH v. 3.3.2016 - I ZR 140/14 - Angebotsmanipulation bei Amazon, para. 30).

Infringement of a first name protected as a trademark by using only the surname

It is true that there is no principle that the public attaches particular importance to a part of a name consisting of a first name and a surname (see BPatG of 24 October 2019 - 27 W (pat) 15/18 - RICCO EGOISTA). However, there are three exceptions to this:

There may be areas of goods in which the public tends to shorten an overall name consisting of a first name and a surname to the surname. In the fashion sector, for example, there is no such practice (BPatG of 14 October 2014 - 27 W (pat) 515/14 - VINCENT MOTEGA/Montega).

On the other hand, the public may attribute special significance to a name element if this name element is unusual (CFI of 22 May 2019 - T-197/16).

Finally, it is recognised that a surname plays a formative role in the assessment of the likelihood of confusion if the earlier trademark formed from the surname has acquired increased distinctiveness through use (BGH of 24 February 2005 - I ZB2/04 - Mey/Ella May; LG Düsseldorf of 29 November 2017 - 2a O 198/16 - Jette Joop).

Example: In the overall designation ‘Blue Motion - Designer pieces by Jette Joop’, the element ‘Jette Joop’ was perceived as independently distinctive. This is because the reputation of the designer Joop has strengthened the sign element ‘Joop’ (Regional Court Düsseldorf of 29 November 2017 - 2a O 198/16 - Jette Joop).

Trade mark infringement through Google Ads

Anyone wishing to use trade mark terms in Google Ads, e.g. as keywords, must observe the principles established by the ECJ and BGH and the ‘principle of exhaustion’.

On 22 January 2009, the Federal Court of Justice ruled in three cases on the question of whether the use of Google Adword keywords protected by trademark or trade mark law is an infringement of trademark law or an infringement of a company's trade mark. In the first two cases, the plaintiffs proceeded from a registered trademark, which, however, in the second case also described the labelled goods. In the third case, the plaintiff proceeded on the basis of its company logo (company name).

Keywords protected as a trademark in Adwords - ‘bananabay’

In the first case (case reference I ZR 125/07 - Bananabay), the defendant supplier of erotic articles had entered the keyword ‘bananabay’ in Google. ‘Bananabay’ is protected as a trademark for the plaintiff, which also sells erotic articles on the Internet under this name. If a designation used as a keyword - as in this case - is identical to a third-party trademark and is also used for goods or services that are identical to those for which the third-party trademark enjoys protection, this constitutes an infringement of trademark law if the use of the protected designation as a keyword constitutes use as a trademark (‘trademark use’). The provisions of German trademark law on the scope of protection of registered trademarks are based on harmonised European law, namely the European Trademark Directive (TMD). The Federal Court of Justice therefore referred this question to the European Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling (see below).

Descriptive keywords in AdWord adverts - ‘PCP-POOL’

In the second case (case reference I ZR 139/07 - PCB-POOL), two companies offering printed circuit boards on the internet faced each other. The plaintiff was protected by the trademark ‘PCB-POOL’. The defendant had registered the letters ‘pcb’ as a keyword with Google, which are understood by the relevant specialist circles as an abbreviation for ‘printed circuit board’. ‘PCP’ is therefore a purely descriptive term and thus not actually eligible for protection as a trademark. The adword application for ‘pcb’ resulted in an advert for the defendant's products appearing in the separate advert block next to the hit list when ‘PCB-POOL’ was entered in the Google search engine. The BGH dismissed the action in this case. As a rule, the trade mark owner cannot prohibit the use of a descriptive indication (in this case ‘pcb’) even if it is used as a trade mark and thereby creates a likelihood of confusion with the protected trade mark. In this case, the BGH assumed that descriptive use was permitted under trade mark law. As a trade mark infringement was to be denied for this reason alone, the legal question referred to the European Court of Justice in proceedings I ZR 125/07 was no longer relevant.

Company name as Adword keyword - ‘Beta Layout’

The third case (case no. I ZR 30/07 - Beta Layout) concerned the use of a company logo. The plaintiff in the second case was also involved here. It has the company name ‘Beta Layout GmbH’. The issue here was that another competitor had entered the term ‘Beta Layout’ as a keyword in Google. In this case, too, whenever an Internet user entered ‘Beta Layout’ as a search term on Google, an advert for the competitor's products appeared next to the list of results. In this case, the Federal Court of Justice confirmed the decision of the Court of Appeal, which had denied an infringement of the company name according tin German trademark law and a corresponding claim for injunctive relief on the grounds that there was no likelihood of confusion required for an infringement of the company name. The internet user does not assume that the advert appearing in the separate advertising block next to the hit list originates from Beta Layout GmbH. In the opinion of the Federal Court of Justice, this finding of fact regarding the understanding of the public was not objectionable. Since the protection of company names, unlike trademark protection, is not based on harmonised European law, a referral to the European Court of Justice was out of the question in these proceedings.

The GC (decision of 23 March 2010, Joined Cases C-236/08, 237/08, 238/08) is also of the opinion that a sign is used as a keyword in a trademark-like manner and therefore constitutes a trademark infringement if the Adword ad gives the impression that there could be an economic connection between the Adwords advertiser and the trademark owner.

Accordingly, the Federal Court of Justice (BGH) found in its decision ‘Bananabay II’ of 13 January 2011, case no. I ZR 125/07,

that the use of a third-party trademark and thus a trademark infringement does not exist if the trademark does not appear in the ad itself, nor does the Adwords ad contain a reference to the trademark owner or its products and the domain does not contain such a reference either.

BGH, judgement of 13 December 2012 - I ZR 217/10 - MOST Pralinen

Keywords protected by trade mark law are also permitted for descriptive domains.

The case: The plaintiff asserted rights from the German trademark ‘MOST’, registered for chocolates. It operated a ‘MOST shop’ under the internet address ‘www.most-shop.com’. It sold confectionery and chocolate products there. The defendant sold gifts, chocolates and chocolate under ‘www.feinkost-geschenke.de’. She placed Adwords adverts for her online shop in January 2007. It had chosen the term ‘chocolates’ as a keyword with the option ‘broad matching keywords’.

The advert therefore also appeared after entering the search term ‘MOST Pralinen (chocolates)’. The advert looked as shown above. The link ‘www.feinkost-geschenke.de’ provided in the advert took the user to the defendant's homepage. No products with the ‘MOST’ logo were sold in the defendant's online shop.

The plaintiff was of the opinion that the defendant had infringed the right to the trademark ‘MOST’ by placing the advert. It filed a claim against the defendant for injunctive relief, among other things. The regional court ruled in favour of the claim. The appeal was unsuccessful. The Federal Court of Justice overturned the appeal judgement and dismissed the action.

The Federal Court of Justice confirmed its case law (Federal Court of Justice, judgement of 13 January 2011 - I ZR 125/07, GRUR 2011, 828 - Bananabay II; judgement of 13 January 2011 - I ZR 46/08, MMR 2011, 608): In ‘keyword advertising’, a trademark infringement is excluded if the advertisement - as in the case in dispute - appears in an advertising block clearly separated from the (‘natural’) hit list and labelled accordingly (the ‘AdWords’ ads) and itself contains neither the trademark nor any other reference to the trademark owner or the products offered under the trademark. This also applies if the advertisement does not refer to the lack of an economic connection between the advertiser and the trademark owner and products of the type offered under the trademark are described in the advertisement with generic terms (in the case in dispute ‘chocolates’ etc.). According to the BGH, this assessment is in line with the case law of the ECJ (most recently ECJ, judgment of 22 September 2011 - C-323/09, GRUR 2011, 1124 - Interflora/M&S Interflora Inc.). Accordingly, it is up to the national court to examine the question of the impairment of the function of origin on the basis of the standards developed by the Court of Justice, taking into account all factors that it considers relevant. The BGH therefore did not consider a referral to the ECJ to be necessary in view of the case law of the Austrian Supreme Court (GRUR Int. 2011, 173, 175 - BergSpechte II) and the French Cour de cassation (GRUR Int. 2011, 625 - CNRRH), which came to different conclusions when assessing Adwords adverts, taking into account the factors they considered relevant.

Google Ads and well-known trademarks - European General Court of 22 September 2011, C-323/09 - Interflora Inc. and others v Marks & Spencer plc and others.

The facts underlying the GC decision of 22 September 2011, C-323/09, Interflora Inc and Others v Marks & Spencer plc and Others were as follows:

Marks & Spencer plc, one of the most important retailers in the UK, operated a flower delivery service and placed Adwords adverts for this purpose, as shown above. Marks & Spencer had booked the keyword ‘interflora’ as one of the triggers for the adverts. The term ‘Interflora’ itself did not appear in the AdWords advert. ‘Interflora’ is registered both as a British trademark and as a Community trademark and, according to the GC's findings, has a ‘high degree of recognition’ in the UK and other EU member states (para. 16). The trade mark proprietor, Interflora Inc (and others), sued for an injunction. The GC ruled on the impairment of the trademark's function as an indication of origin (para. 50):

‘In this context, as stated in paragraph 44 of the present judgment, the relevant public is composed of internet users who are reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect. Thus, the fact that some internet users may have had difficulty in recognising that the service offered by M & S has nothing to do with that offered by Interflora is not sufficient to establish amicable settlement of the function of indicating origin.

As regards the detriment to the distinctive character of a trademark with a reputation, the GC stated in this decision (para. 95):

By contrast, the proprietor of a well-known trademark may not, inter alia, prohibit competitors from using keywords corresponding to that trademark to make an advertisement appear which, without offering a mere imitation of goods or services of the proprietor of that trademark, without causing dilution or disparagement and without otherwise adversely affecting the functions of the well-known trademark, proposes an alternative to the goods or services of its proprietor.

Even the owner of a distinctive trademark with a reputation cannot therefore prohibit others from using identical keywords if the advertised products are not imitations, no dilution is caused and the other trademark functions are not impaired.

According to the GC, booking a trademark as a keyword is, in principle, a trademark use, even if the trademark does not appear in the ad itself. However, in order to constitute a trade mark infringement, one of the trade mark functions (origin function, advertising function, investment function) must also be impaired, according to the GC. The GC did not consider these trade mark functions to be infringed in the case to be decided. According to the GC, whether a trade mark infringement has occurred depends on how the advertisement is designed. It is present if

- it is difficult for a normal internet user to recognise whether the products originate from the trademark owner or an affiliated company, or from a third party

- the AdWords advert is so vague that the normal Internet user cannot recognise whether the advertiser is affiliated with the trademark owner.

This means that, as a rule, there is no trademark infringement if the trademark is booked as a keyword (or if the trademark was selected by Google itself as the trigger for the ad placement as a result of the keyword option ‘broadly matching keywords’), but is not visible in the ad itself. In the case of company trademarks, an infringement is also ruled out if the company trademark is not visible in the advert itself (BGH I ZR 30/07 - Beta Layout).

Use of trademarks in domain and Google Ads by a reseller - BGH of 28 June 2018, I ZR 236/16 - keine-vorwerk-vertretung

An online retailer for used Vorwerk hoovers and Vorwerk accessories had connected his online shop under the domain ‘keine-vorwerk-vertretung.de’. He also offered accessories from other trademarks in his online shop. He placed the Google ad shown here. The plaintiff claimed that this was an infringement of the well-known trademark ‘Vorwerk’. The defendant invoked the principle of exhaustion: as the goods offered had been sold in the EU with the consent of the trade mark owner, the trade mark right for resale was ‘exhausted’. The goods could therefore also be used in advertising.

In its AIDOL decision, the BGH had only assumed exhaustion for websites on which original products were also offered. The BGH has now relativised this for the situation of resellers who also sell products from other manufacturers in addition to original goods: In these cases, it depends on whether legitimate interests of the trade mark owner are safeguarded. After all, a reseller of products from several trademarks must use these trademarks to draw attention to its business. The BGH also assumed exhaustion in this case. The ‘Vorwerk’ trademark was also permitted to be used in the Adwords advert, even if products other than original Vorwerk products were also advertised in the online shop. However, the BGH also doubted whether the trade mark owner could object to the use of the name on legitimate grounds in accordance with Section 24 II MarkenG. The BGH tended to regard the use of the trademark in the Google ad as inadmissible and referred the case back to the Higher Regional Court of Cologne. The Higher Regional Court of Cologne agreed: The relevant public would understand the references on the defendant's website to mean that only original products of the plaintiff were offered under the trademarks ‘Kobold’ and ‘Tiger’ (OLG Cologne of 21 June 2021 - I-6 U 131/15 - keine-Vorwerk-Vertretung II).

Trademark infringement through search engine optimization (SEO)

The browser title - defined in the title tag

The browser title of a web page is defined in the HTML title tag and is read by every search engine. It is considered an important factor in search engine optimization. Google often takes the title tag as part of the title in the search result short texts ("snippets").

Keywords are therefore popular in the title tag for search engine optimization. Third-party brands or company logos (e.g. company names) are often placed there, especially if these terms are well-known and popular or if the brands are sold by the company itself. Portals and platforms thrive on attracting traffic for popular brands and companies. They also regularly do this by including these terms in the title tags. This is dangerous.

The starting point of case law for the question of trademark infringement is the snippet itself, not the linked website!

The question of whether an infringement is to be judged on the basis of the short snippet - the case law refers to this as the "hit list" - or whether it is only the complete website to be clicked on under a link that is decisive, has long been decided. In principle, case law has focused on the snippets in cases involving infringing metatags. The fact that the content of the website to be clicked on eliminates the risk of confusion under trademark law is irrelevant (BGH ruling dated May 18, 2006 - I ZR 183/03 - Impuls; BGH ruling dated February 8, 2007 - I ZR 77/04 - AIDOL). This is also assumed to be the case with title tags (OLG Frankfurt am Main, decision dated March 3, 2009 - 6 W 29/09; OLG Frankfurt am Main, decision dated January 10, 2008 - 6 U 177/07). The search result snippet is therefore decisive for the question of infringing use of trademarks and company logos. The case law considers the content of the linked website itself to be irrelevant.

Foreign trademarks in title tags - the "exhaustion principle" in trademark law

Including third-party trademarks in the title tag without the consent of the trademark owner is generally a trademark infringement if the goods protected by the trademark and the goods offered on the search result snippet are at least similar (BGH judgment dated February 4, 2010 - I ZR 51/08 - POWER BALL).

However, according to the so-called "exhaustion principle", it is permissible to include another's trademark in the title tag if the trademark's goods are actually offered on this very website (cf. BGH judgment of 8.2.2007 - I ZR 77/04 - AIDOL). Then the rights of the trademark owner are "exhausted". Prerequisite: The goods offered there were sold for the first time within the EU with the consent of the trademark owner. If, however, the trademark owner first sold the goods to a gray dealer in the USA, for example, and this dealer then sells the goods to another dealer in the EU without the trademark owner's consent, the further sale is prohibited (e.g. BGH of March 15, 2012 I ZR 137/10 - CONVERSE II). Another requirement for exhaustion: The false impression must not be created that one has a special business relationship with the trademark owner, e.g. as an authorized dealer (cf. BGH judgment of 7.11.2002 - I ZR 202/00 - Mitsubishi). Thus, if the trademark is combined with the term "online store" in the title tag (e.g. "LEVI'S ONLINE SHOP), this would be inadmissible. This would falsely suggest that one is an authorized dealer of the trademark owner or that one has a special business relationship as the operator of the trademark owner's online store.

Permitted trademark naming according to § 23 No. 1 and 2 MarkenG /Art. 12 a) and b) Union Trademark Regulation

The use of brand-similar or brand-identical terms to describe products is also permitted. For example, "pcb" as a common abbreviation for "printed circuit board" is not an infringement of the trademark "PCB-POOL", BGH v. 22.1.2009 I ZR 139/07- pcb. The same applies to descriptive statements customary in the trade or in permissible (i.e., if there is no trademark infringement - BGH v. 4.2.2010 - POWER BALL) comparative advertising. Trademarks may also be mentioned if this is necessary to describe Ersat lines.

Foreign company names ("company trademarks") in the title tag

Including other people's company names (company trademarks) in a title tag is generally a violation of a company trademark if the opposing designations and the opposing industries are at least similar. A designation in itself is only protected as a corporate designation against use for at least similar industries. However, outside the similarity of industries, the designation is protected as a name if it is used identically or "almost identically" and "confusion as to allocation" arises (BGH, judgment of November 9, 2011 - I ZR 150/09 - Basler Haar-Kosmetik). What is meant by this is confusion about the bearer of the name.

According to case law, it is sufficient for the company name to serve as a "pilot," i.e., to direct the Internet user to the website of the party using the third-party company name in the browser title (OLG Hamburg, judgment dated March 2, 2010 - 5 W 17/10). It is therefore sufficient for a company trademark infringement if the same services appear in the snippet of the search engine result as those offered by the owner of the company trademark and the Internet user thereby confuses these offers. The content of the respective website itself is then no longer relevant (BGH judgment dated May 18, 2006 - I ZR 183/03 - Impuls; OLG Frankfurt am Main, judgment dated January 10, 2008 - 6 U 177/07).

Disclaimer does not prevent infringement

In order to assess whether a title tag infringes another person's trademark or a company trademark, case law does not focus on the website in question, but on the search result snippet. A disclaimer (such as: "The owner of this website has no business relationship with the owner of trademark X or company Y") on the website itself can therefore no longer avert an infringement. It is uncertain whether a search engine will accept the title tag unchanged. If such a snippet violates third-party trademarks or company logos, the person who has inserted a disclaimer in the title tag cannot claim that he has no influence on the snippet compiled by Google. If you include certain keywords in the title tag, these keywords are your own information and not that of the search engine. One is liable for this without restriction (BGH judgment of 4.2.2010 - I ZR 51/08 - POWER BALL). The right to cease and desist under trademark law and also the right to information do not require any fault anyway.

Trade mark infringement through domain

Trade mark infringement only for connected domains

The use of a domain can also infringe a trademark. However, the prerequisite for the infringement of a trademark by a domain is that the domain is connected, i.e. a website is accessible on which a company is represented and/or products are advertised. The mere registration of a domain that is not connected cannot infringe a trademark because there is no connection to a product or a company. In such cases, however, an infringement of the right to a name by a domain is conceivable.

Anyone wishing to use a domain for a website must therefore check whether they are infringing a third-party trademark or company name. It does not matter whether the domain is intended to identify a company (which will usually be the case) or specific products on the website. This is because the owner of a trademark or a company sign can defend himself against both company-marking (‘company-marking-like’) and product-marking (‘trademark-like’) use of his protected sign. The same applies if the domain characterises the products offered on the website (see § 14 III No. 5 MarkenG or Art. 9 III d) UMV). Particularly in the case of services, a domain often characterises both the company and the products offered.

Example: A music school offered music lessons under the domain ‘musikschule-pelikan.de’. The individual services (accordion, brass instruments, electric bass etc.) were presented on the homepage in a column under the heading ‘Our offer’. This infringed the trademark ‘Pelikan’, registered for teaching aids, among other things. This is because the domain not only identified the music school but also its services listed on the homepage (BGH of 19 April 2012 - I ZR 86/10 - Pelikan).

Domain parking can be sufficient for a trade mark infringement. However, the domain must refer to the goods or services offered on the connected domain parking page. According to case law, it is sufficient if, for example, the reference ‘sponsored links on the topic ...’ appears on the website in question, the trademark in question is mentioned and the links lead to comparable products from other providers (BGH, judgement of 18 November 2010 - I ZR 155/09 Sedo).

No all-encompassing ban on any use in the event of trade mark infringement through a domain

Anyone whose trademark rights are infringed by a domain cannot have the use of the domain prohibited ‘per se’, i.e. in every conceivable way (e.g. BGH judgement of 18 December 2008 - I ZR 200/06 - Augsburger Puppenkiste). Nor can he demand the cancellation or even transfer of the domain to himself. He can only have the domain holder prohibited by a court from using the domain in exactly the same way as it infringes his trademark. The domain holder therefore does not have to transfer the infringing domain to the rights holder or delete it (BGH judgement of 9 November 2011 - I ZR 150/09 - Basler Haar-Kosmetik).

Exception: name right infringement through domain

The situation is different in the case of an infringement of name rights by a domain. In this case, there is a cancellation claim.

Consequences of a trade mark infringement

Injunctive relief and claim for damages

Anyone who infringes another person's trademark can be sued for injunctive relief in accordance with Section 14 II MarkenG or Art. 9 II UMV. In practice, this claim is asserted out of court by means of a warning letter for trade mark infringement and in court by means of proceedings for an interim injunction or an action. In addition, the infringed trademark owner (but not the trademark licence holder) is entitled to damages.

One way of calculating damages in trade mark law is the so-called ‘licence analogy’ or according to the infringer's profit. To do this, he needs the infringer's details. For this purpose, the law also grants the infringed party a right to information (see below). If the injured party calculates his damages according to the licence analogy, he can also demand his (fictitious) lost licence payments from the infringer according to the principles of unjust enrichment. This claim, like the claim for injunctive relief, is not dependent on fault. The infringer is unjustly enriched by the licence fees saved (BGH GRUR 2001, 1156 - Der grüne Punkt).

Right to information in the event of trade mark infringement

In addition to claims for injunctive relief and damages, the owner of a trademark is entitled to a right to information. This is primarily intended to help the infringed party to quantify the damage suffered as a result of the infringement (so-called ‘accessory right to information’). In addition, in the event of an infringement of an industrial property right, the supply chain and the distribution channel of the goods infringing the trade mark right should be disclosed (‘independent right to information’).

Read here: Content and scope of the right to information in the event of trade mark infringements

Author: Thomas Seifried, trademark lawyer Europe and trademark lawyer Germany

This might also interest you:

Received a warning letter in trademark law?

Everything you need to know about a warning letter in trademark law

Trademark opposition

Trademark registration

Trade mark infringement

When is there a trademark infringement of a eu or german trademark and what are the consequences?

Cancellation of a German or an EU trademark at the EUIPO and DPMA

"Distinctive character" in trademark law

What does "distinctive character" in trademark law mean?

![[Translate to English:] Markenrechtsverletzung Einzelbuchstaben Barbie Detailansicht eines Kinderschuhs mit glitzerndem Buchstaben B](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/7/csm_Barbie_B_e6ed7da9b5.jpg)