Author: Thomas Seifried, trademark lawyer Europe and trademark lawyer Germany

Your trademark lawyer in Europe

Free initial assessment of your case

Trademark lawyer Thomas Seifried has over 20 years of experience in European trademark law and has also been a German specialist attorney for intellectual property law ("Fachanwalt fuer gewerblichen Rechtsschutz") since 2007. He is an author of specialized books and has conducted many successful proceedings before courts and the trademark offices.

Contact us

Free initial assessment

Our initial consultation in trademark law is free of charge.

+49 69 9150760

Here you can send us your documents. We will treat your request strictly confidential.

Trademark oppositions before EUIPO and DPMA

What you need to know about trademark oppositions before EUIPO and DPMA against the registration of a German trademark or an EU trademark

Trademark cancellations at the EUIPO and DPMA

What you need to know about a cancellation of a trademark at the EUIPO and DPMA

Why should you register a trademark?

Trademark registration creates prohibition right

First of all, you do not need a trademark to use a "sign", e.g. a name or logo. It certainly does not follow from the registration of your trademark that you can use it without risk. This is because a trade mark office (DPMA or EUIPO) only examines the absolute grounds for refusal, but not the relative grounds for refusal. Accordingly, the application for a trademark itself can already constitute an infringement of trademark rights.

Rather, a trademark is a prohibition right: the owner of a trademark can prohibit others from using the trademark identically or similarly. Anyone who sets up a business and wants to sell goods or services under a certain sign is well advised to register this sign as a trademark in the countries in which they want to use it as a trademark. This is the only way to prevent others from using this trademark.

Creation of trademark protection through registration

Trademark protection in Germany is obtained by registering a sign in the trademark register of the German Patent and Trademark Office (DPMA). More or less uniform trademark protection in the 27 member states of the European Union is obtained by registering a EU trade mark with the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO).

The international registration of a German trademark or a EU trade mark with the WIPO gives the trademark the same protection in the member states of the Madrid Agreement as a trademark of the respective member state. At present, 84 states and confederations of states are contracting parties to the Madrid system, including the European Union.

Costs of a trademark application

Overview

| German trademark | EU trade mark | Internationally Registered trademark | |

| Costs of the Trademark Office | € 290,00 for up to three classes of goods | € 850.00 for one class of goods, € 900.00 for two classes of goods, € 1,050.00 for three classes of goods | Depending on the number of classes and the protected area |

| Research costs | Dependent on the research effort | Dependent on the research effort | Dependent on the research effort |

| Our legal fees for the application | 295.00 (plus VAT)1 for up to three classes of goods | € 650.00 (plus VAT)1 for up to three classes of goods | Depending on the number of classes and the protected area |

1) We exclusively advise and represent entrepreneurs within the meaning of § 14 BGB.

What can be protected as a German trademark or a EU trade mark?

In principle, words, names, pictures, letter combinations, numbers, acoustic sound sequences, three-dimensional shapes, product packaging, color combinations, tactile marks, and theoretically also odors can be protected as a German trademark or a EU trade mark.

The most important requirement for regsitration of a trademark is distinctiveness. However, the trademark itself must be capable of distinguishing other goods or services.

Descriptive indications cannot be registered as a German trademark or a EU trade mark. Furthermore, the trademark may not be deceptive about characteristics of the goods/services, be contrary to public policy, or contain official coats of arms or seals. The use of official coats of arms, flags, seals, test marks is also an administrative offense and thus punishable by law. Official test marks generally bear a coat of arms, for example a federal eagle.

Types of trademarks

Trademarks can be differentiated according to their geographical area of protection, e.g. as

- German registered trademark

- German utility mark (rare)

- European Union trademark (the "European trademark"; formerly: Community trademark)

- IR trademark, internationally registered trademark

Trade marks can also be distinguished by their elements:

- Single-letter trademarks consist of only one letter. Their scope of protection is limited, so there is rarely a likelihood of confusion with single letter marks.

- Word marks consist of only one or more words or signs without graphic elements

- Word/figurative marks (terminology of the DPMA and German case law) or figurative marks (terminology of the EUIPO, also for marks with word elements) are marks that contain graphic elements in addition to words or signs. The scope of protection of word/figurative marks is often less than their owners believe.

- Pure figurative marks do not contain any words or signs.

- 3D trademarks are a subset of figurative trademarks. The protectability of 3D trademarks is often problematic.

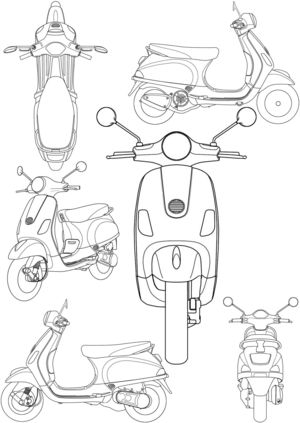

Example: The Board of Appeal of the EUIPO held that the 3D mark of the shape of a "Vespa" scooter was not protectable due to a lack of distinctive character and declared the mark invalid. In its judgment of 29.11.2023 in Case T-19/22 - Piaggio & C. SpA v EUIPO, the General Court of the European Union annulled the decision of invalidity.

- Abstract color marks (rare!) claim protection for a specific color for specific goods or services.

- A position mark claims protection for a specific position on a product.

- A certification mark, also known as a European Union certification mark, in turn guarantees certain characteristics of a product or service.

Trademarks can also be distinguished according to the degree of recognition. A

has a significantly broader scope of protection than other trademarks.

Application for certification marks and EU certification mark

With a German certification mark or a European Union certification mark (§§ 106a MarkenG ff. or Art. 83 ff. Union Trademark Regulation), the trademark owner can grant certain characteristics of the goods and services claimed by the trademark. Such characteristics can be The material, the method of manufacture or provision of the service, the quality, or the accuracy. A geographical origin cannot be guaranteed. A certification mark must, of course, also have distinctive character and be capable of serving as an indication of origin (see CFI of 13.07.2018 - T-825/16 - Pallas Halloumi, not final).

Only those who are neutral with regard to the goods and services for which the trademark is intended can become the owner of a certification mark. This means that the owner of a certification mark must not offer these goods or services and must not have any economic interest in the relevant market. He must also not be economically connected to the manufacturer of the goods or provider of the services. The trademark offices check these requirements independently.

Example:

Anyone applying for an EU trademark for

"Testing, authentication and quality control"

(in Nice Class 42) may not certify certain goods or services themselves or through third parties (see Art. 83 II EUTMR).

When applying for a certification mark (Sections 106a ff. MarkenG) or the EU certification mark (Art. 83 ff. UMV), a trademark statute must be submitted. The applicant for an EU certification mark must define the characteristics of the goods or services in the regulations governing use. The trademark statutes must also contain the conditions for use and name the persons who may use the certification mark. This also means that the trademark statutes must define precise sanctions for infringements of the trademark statutes (see Section 106d II No. 6 MarkenG and Art. 84 II 2 EUTMR). If trademark regulations are not submitted within two months of the application, the Office will reject the deregistration (Section 106e I MarkenG and Art. 85 II EUTMR). The trademark statutes are published in the trademark register.

Necessary steps of a trademark application

Seven steps to trademark registration

- Step 1: Determine the type of trademark you want to register

- Step 2: Define the goods or services for which your trademark is to be protected. These determine the list of goods and services of the trademark.

- Step 3: Check the protectability (i.e. distinctiveness) of the trademark for these goods and services

- Step 4: Determine the geographical areas in which your trademark is to be protected. This will determine which trademark(s) you need to register.

- Step 5: Carry out a trademark search - do older identical or similar rights stand in the way of a trademark registration?

- Step 6: Select a suitable trademark office: German trademark, EU trademark, Benelux trademark, IR trademark, national foreign trademark?

- Step 7: Apply for a trademark

Application for a German trademark at the DPMA

Registered trademark under the Trademark Act - requirements for protection, duration of protection, scope of protection and typical problems

An application for registration of a German trademark is filed with the German Patent and Trademark Office, DPMA. A sign protected as a registered German trademark grants its owner the right to allow others to use this or a similar sign for the products (goods or services) registered in the trademark register. Protection arises upon entry in the register of the DPMA (Section 4 No. 1 MarkenG) and begins retroactively from the date of application (Section 47 I MarkenG). Protection lasts for 10 years. The term of protection can be extended as often as required for a further 10 years. In contrast to other property rights, trademarks can live forever.

Overview: The German registered trademark

- Prerequisite for protection: registration (lack of absolute grounds for refusal, in particular lack of distinctiveness and "descriptive indications"; lack of relative grounds for refusal, Section 9 et seq. MarkenG, conflicting earlier rights)

- Term of protection: Ten years from trademark application (Section 47 I MarkenG), with unlimited renewal options for a further ten years in each case

- Scope of protection: Interaction of distinctiveness and the similarity of the opposing signs and products (goods or services)

- Typical problems with infringement: "trademark use": Is the sign understood as a function of origin or as "decorative use" to shape the product?

Advantages of the (German) registered trademark compared to the EU trademark

The German registered trademark has some advantages for the owner compared to the EU trademark, especially if it is a "weak" trademark with only low distinctiveness. For example, anyone who takes action against a trademark infringer on the basis of a registered German trademark does not have to fear that the trademark infringer will attack the trademark in a lawsuit with a counterclaim for a declaration of invalidity due to a lack of distinctiveness. The MakenG does not provide for such a possibility of a counterclaim for a declaration of invalidity for lack of distinctive character in the case of an infringement of an EU trademark (see Art. 59 I a EUTMR). The owner of a German trademark only has to fear invalidity proceedings before the DPMA. In most cases, however, such proceedings will have no influence on trademark infringement proceedings because the courts only rarely stay the proceedings until the DPMA has reached a decision. After the expiry of ten years, the owner of a weak German trademark no longer has to fear a nullity application at all (see Section 50 II MarkenG). There is no comparable provision for EU trademarks.

Applying for an EU trade mark at the EUIPO

Conditions for protection, term of protection, scope of protection and typical problems

European EU trade marks are applied for at the European Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) in Alicante.

- Prerequisite for protection: Registration (lack of grounds for refusal, e.g. absolute grounds for refusal, Art. 7 European Union Trade Mark Regulation (EUTMR), in particular lack of distinctive character and flatly descriptive indications and relative grounds for refusal, Art. 8 European Union Trade Mark Regulation (EUTMR), conflicting earlier rights)

- Duration of protection: Ten years from application, with unlimited renewal options for a further ten years ("trademarks do not die")

- Scope of protection: Interaction of distinctiveness, brand recognition (= strengthening of distinctiveness), similarity of the opposing signs and products (goods or services)

- Problems in the event of infringement: Often use as a trademark: If the sign is understood as an indication of origin ("origin function of the trademark") or to identify a company or part of a company (then company logo) or product-designing as decorative use; risk of confusion

The "seniority" of an EU trade mark - claiming the seniority of a national trademark

A special feature of the EU trademark is "seniority" (Art. 39 f. EUTMR): The proprietor of an EU trademark who is also the proprietor of an identical, earlier national trademark can declare to the EUIPO that he claims the "seniority", i.e. the seniority (filing or priority date), of the national trademark. The purpose of seniority: The trademark owner should not be disadvantaged by not renewing or renouncing the national trademark. Seniority means that the national trademark lives on in the EU trademark from the date of application. This is intended to prevent multiple protection of the same sign. This saves the trademark owner time and money. A prerequisite for the effect of seniority is therefore that the trademark owner actually surrenders his national trademark, i.e. renounces the trademark or allows it to lapse (i.e. expire) (see Art. 39 III EUTMR).

Exception: Earlier trademark invalid or expired

However, the earlier seniority of the national trademark cannot be claimed if this earlier trademark is declared invalid or revoked (Art 39 IV EUTMR).

If a trademark proprietor surrenders an earlier national trademark or allows it to lapse, but the trademark could have already been revoked at that time due to non-use, the EU trademark loses the seniority of the earlier trademark, see Art 4 of Directive (EU) 2015/2436 (EU Trademark Directive). The same applies if the earlier national trademark is declared invalid. The revocation or invalidity of the earlier national trademark must have occurred at the time of the surrender or expiry (BGH of 8.11.2018 - I ZR 126/15 - PUC II; ECJ of 19.4.2018 - C-148/17 - Peek & Cloppenburg Hamburg/Peek & Cloppenburg Düsseldorf).

Claiming a foreign priority

Filing date brought earlier by foreign first filing

Under certain circumstances, international treaties allow the applicant of a trademark to claim the earlier filing date of an identical trademark filed no more than six months earlier in another country. The trademark is then treated as if it had already been applied for at the time of the earlier foreign application. The most important international treaty is the Paris Convention. (PARIS CONVENTION). The Protocol to the Madrid Agreement (PMMA) also contains important priority rules. Especially if the trademark register in the country of first registration cannot be searched electronically, such a strategy is ideal for companies that initially wish to conceal their trademark registration. The Kingdom of Tonga, for example, is a member of the Paris Convention.

Example: Google's US trademark 98202646 "GEMINI" claims the priority of a trademark TOM202304493 "GEMINI" from Tonga

Even before Google applied for the US trademark 98202646 "GEMINI" at the United States Patent and Trademark Office on 28.09.2023, Google had applied for a trademark TOM202304493 "GEMINI" at the Intellectual Property Office of the Ministry of Trade & Economic Development Kingdom of Tonga on 09.05.2023. Google indicated this priority when applying for the US trademark 98202646 "GEMINI", so that the US trademark claims the filing date of the Tonga trademark. An electronic trademark register does not exist in Tonga. Extracts from the trademark register in Tonga can only be obtained through local attorneys in Tonga. This costs from USD 350.00 per extract. However, anyone wishing to apply for an extract from the trademark register must already know the trademark in question. A trademark search for potentially conflicting trademarks is therefore actually impossible. Anyone who initially applies for a trademark in Tonga can therefore initially keep this trademark secret for up to six months before claiming its filing date in a later "stealth trademark" application.

The absolute grounds for refusal in trademark registration

Anyone applying to register a sign or designation as a German trademark or EU trademark must overcome the hurdles of absolute grounds for refusal. These determine whether a sign can be registered as a trademark at all. The trademark offices check these absolute grounds for refusal themselves. If there is an absolute ground for refusal, the trademark office rejects the trademark application and the trademark applied for is not registered. If the absolute grounds for refusal only apply to some of the goods and services applied for the trademark, the trademark office will reject the trademark application in part.

The most important absolute grounds for refusal in a trademark application

In practice, the most important absolute grounds for refusal are lack of distinctiveness (Section 8 II No. 1 MarkenG or Art. 7 I b) of the European Union Trade Mark Regulation) and descriptive indications that require a declaration of availability. (§ 8 II No. 2 MarkenG or Art. Art. 7 I c) European Union Trademark Regulation). Both groups of cases are usually examined together by the trademark offices. Signs that are absolutely unprotectable under Section 8 MarkenG or Art. 7 (1) b) to k) EU Trademark Regulation are not registered as trademarks by the German Patent and Trademark Office (DPMA) and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO). Such trademark applications are rejected. Signs are not registered as EU trademarks even if these absolute grounds for refusal exist in only one part of the European Union, Art. 7 (2) EUTMR. In contrast to the absolute grounds for refusal, the "relative grounds for refusal" are only examined by the offices on the initiative of the proprietors of earlier rights. Practically relevant absolute grounds for refusal are also designations that have become customary pursuant to Section 8 (2) No. 3 MarkenG and Art. 7 (1) d EUTMR. This group of cases mainly concerns generic names.

Distinctive character in trademark law

The most important obstacle to a trademark application: Lack of distinctiveness

Distinctiveness is the suitability of a trademark to distinguish the applied-for goods or services of one company from those of another company. In the case of company marks, distinctiveness means the suitability of the mark to distinguish one company from another for the industry in question. Distinctiveness is a prerequisite for protectability in the case of trademarks and corporate identifiers.

However, what has been registered as a trademark is considered to have at least weak original distinctiveness by the relvant courts (BGH of 02.042009 - I ZR 209/06 - POST/RegioPost). Registered trademarks are therefore always considered to be eligible for protection. The mere objection in trademark infringement proceedings that the registered trademark is not distinctive at all and therefore not protectable is therefore unsuitable. In this case, only nullity proceedings before the Office or - in the case of EU trademarks - an action for annulment can help (cf. Art. 58 I UMV).

Distinctiveness as defined by case law

The German Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof - BGH) defines distinctiveness thus (BGHZ 167, 278, para 18 - FUSSBALL WM 2006):

"Distinctiveness is the inherent (concrete) capacity of a sign to be perceived by the public as a means of distinguishing the goods or services in question as originating from a particular company and thus distinguishing those goods or services from those of other companies."

The essential function of a trade mark is to guarantee to the consumer or end user the identity of the origin of the goods or services designated by the mark by enabling him to distinguish those goods or services from goods or services of a different origin without any possibility of confusion. By virtue of its distinctive character, a trade mark may identify the product or service covered by it as originating from a particular company and thus enable that product or service to be distinguished from those of other companies (ECJ, Judgment of. 16.9.2015 - C-215/14 - Société des Produits Nestlé/Cadbury UK Ltd).

Distinctiveness therefore means: a sign can be perceived as an indication of origin at all. The sign should be able to identify the goods or services concerned as originating from a particular company.

Examination of distinctiveness by trademark offices

Distinctiveness is examined independently by the German Patent and Trademark Office (DPMA) and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) for each of the goods or services applied for. If the distinctive character is lacking for a product, this indicates the lack of distinctive character for the associated service (BGH, of 13. 09.2012, I ZB 68/11 - Deutschlands schönste Seiten). Criteria other than distinctiveness are irrelevant. It is therefore irrelevant, for example, a "certain excess of imagination" of the sign applied for (ECJ of 21.10.2004, C-64/02 - DAS PRINZIP DER BEQUEMLICHKEIT). Designations such as "super" or "ideal" are usually not distinctive.

Example

"SUPERgirl" is not registrable for many goods and services (BGH GRUR 2011,230 - SUPERgirl)

Distinctiveness through intention to use? ECJ v. 12.9.2019 - C-541/18

Lack of distinctiveness can only be overcome by proving reputation (or what corresponds to that for EU trademark law: proof of acquired distinctiveness). Sometimes, however, applicants try to overcome the lack of distinctiveness in another way. They then claim in the application procedure that they want to use the applied for sign in a less likely way.

Example: In a German trademark application, the applicant seeks protection for the term.

"#darferdas?"

for, among other things, clothing. The DPMA rejected the application. The designation is not protectable for clothing, the distinctive character would be missing. The designation would be regarded as a decoration and not as an indication of origin. The company said that it was correct to take into account not only the most probable form of use, but also other obvious forms of use. For example, she would also like to put the designation "#darferdas?" on labels. In a use on labels, one would see an indication of origin. In the oral proceedings before the Federal Patent Court, the applicant submitted as an example of use a T-shirt with a sewn-in inner label with the inscription "#darferdas?".

In fact, the BGH had in the past considered the use of a sign on a label as an indication of origin (e.g. BGH v. 10.11.2016 - I ZR 191/15 - Sierpinksi-Dreieck). It was therefore now not so sure whether it had to consider other obvious uses in addition to the most likely one. The BGH referred the matter to the ECJ. The latter replied that the authorities (in the case the DPMA) must take into account all relevant types of use and examine whether in these types of use the sign is considered as an indication of origin (then protectable) or only as a decorative use (ECJ v. 12.9.2019 - C-541/18).

Distinctiveness of word and figurative marks

Distinctiveness is always assessed on the basis of the overall sign. This must be taken into account in the case of word and figurative marks. The mere fact that a word/figurative mark is registered therefore says nothing about whether the isolated word component is also eligible for protection. This, in turn, must be assessed on the basis of the distinctiveness of the word element for the goods or services claimed.

Example OLG Frankfurt/M. v. 4.10.2012 - 6 U 217/11 - fishtailparkas:

The word element of the German word-picture mark No. 302009000717 "fishtailparkas" is not protectable due to lack of distinctiveness.

is descriptive for "outerwear" and therefore not protectable as a word and without graphic components (OLG Frankfurt v. 4.10.2012 - 6 U 217/11).

Examples of lack of distinctiveness

Example Federal Patent Court (BPatG) v. 23.11.2010 - 27 W (pat) 16/10 - MATCHWEAR:

The trademark applicant applied for registration of the designation "MATCHWEAR" as a word mark in the trademark register at the German Patent and Trademark Office (DPMA). The applicant sought protection for, among other things, "clothing, jewelry, jewelry goods as well as textiles and bedding textiles." The DPMA therefore refused registration. It considered the designation "MATCHWEAR" to be descriptive and thus not registrable: "MATCHWEAR" meant "competition clothing" and was therefore merely descriptive. The Federal Patent Court ruled in favor of the DPMA, stating that "MATCHWEAR" lacked distinctiveness (see Sec. 8 II No. 1 MarkenG). In addition, "MATCHWEAR" was a descriptive indication ineligible for protection under Section 8 II No. 2 MarkenG. Therefore, the trademark could not be registered. Only for the field of "bed textiles" the designation is not descriptive and thus only registrable for bed textiles.

Example BGH v. 17.10.2013 - I ZB 11/13 - grill meister

The Federal Supreme Court denied the distinctive character of the applied word and figurative mark forClass 29: Meat, fish, poultry and game; meat extracts; preserved, frozen, dried and cooked fruits and vegetables; jellies, jams, compotes; dairy products; edible oils and fats;

Class 30: Flours and preparations made from cereals, bread; honey; salt, mustard; vinegar; sauces (condiments); spices;

Class 31: Agricultural, horticultural products; live animals; fresh fruits and vegetables; live plants;

Class 43: Services for providing food and drink for guests.

Example BGH v. 21.2.2008 - I ZB 24/05 (BPatG) VISAGE

The term "VISAGE" is descriptive for face cream and thus has no distinctive character. This is because the term "Visage" is also used colloquially in German for face.

Example EuG v. 6.4.2017 - T-219/16 - ViSAGE

"ViSAGE" is also not protectable for devices for body care, massage devices, facial saunas and cosmetic ultraviolet lamps

Example BGH v. 27.4.2006 - I ZB 96/05 (BPatG) FOOTBALL WM 2006

The soccer world association FIFA had registered the term "FUSSBALL WM 2006" as a trademark for a whole range of goods and services. These registrations were largely cancelled again in 2006 because the term "FUSSBALL WM 2006" was descriptive not only for the sports event "Football World Cup 2006", but also for all goods and services associated with this sports event.

Strengthening the distinctive character through use

The more original and individual a designation is for the product in question, the "stronger" it is. The distinctiveness of a brand can increase if the brand becomes better known, for example through intensive advertising. The brand then becomes "stronger," so to speak. A designation that is descriptive in itself and would be ineligible for protection can therefore nevertheless be registered as a trademark if it has acquired "reputation in the trade" (see below). Likewise, a weak or averagely distinctive trademark may have strengthened its distinctiveness through advertising.

Registered trademarks at least weakly original distinctive character

What is registered is considered to be at least weakly distinctive (BGH v. 02.042009 - I ZR 209/06 - POST/RegioPost). Registered trademarks are therefore considered to be eligible for protection. The objection in trademark infringement proceedings that the registered trademark is not distinctive at all and therefore not protectable is therefore unsuitable.

Subsequent loss of distinctiveness

However, a trademark can also lose its distinctive character again if it has become descriptive for the goods or services for which it is protected due to its high degree of recognition.

Example BGH v. 23.10.2008 - I ZB 48/07 - POST II:

The designation "POST" was registered for, among other things, mail delivery services for Deutsche Post AG. Several competitors of Deutsche Post AG filed applications for cancellation against this: They argued that the trademark was now merely descriptive of these services and could no longer be protected. The trademark was initially canceled. However, the Federal Supreme Court referred the case back to the Federal Patent Court, which must now decide whether the descriptive term "POST" for mail delivery is so well known that it is nevertheless understood as an indication of the origin of the service from the company "Deutsche Post AG".

Descriptive indications which must be kept free, Sec. 8 (2) No. 2 MarkenG/Art. 7 (1) c UMV

Descriptive indications are an absolute ground for refusal in a trademark application according to Sec. 8 (2) No. 2 MarkenG/Art. 7 (1) c Union Trade Mark Regulation (UMV). They more or less describe the goods or services according to their nature, quantity or time of origin. Such indications need to be kept free and cannot be registered as an EU or German trademark.

It is in the interest of the general public that all signs or indications which are descriptive of characteristics of the goods or services applied for may be freely used by all undertakings (cf. ECJ v. 12.2.2004 - C-265/00 - BIOMILD, para. 35). It is sufficient that a word mark designates a characteristic of the products concerned in a customary and intelligible manner (ECJ v. 23.10.2003 - Case C-191/01-DOUBLEMINT, para. 32). Here, the understanding of the trade alone may also be sufficient. Any competitor must be able to freely use descriptive indications (ECJ v. 9.12.2009 - C-494/08 - PRANAHAUS, para. 25; BPatG v. 14.11.2012 - 28 W (pat) 518/11) - protectability of the designation M).

Trademark application for advertising slogans

Advertising slogans are not subject to stricter requirements than other designations (ECJ, judgment of 21.10.2004 - C-64/02 - DAS PRINZIP DER BEQUEMLICHKEIT). Ultimately, however, advertising slogans must also be perceived as an indication of the business origin (ECJ, judgment of 12.7.2012 - C-311/11 P Smart Technologies ./. OHIM - WIR MACHEN DAS BESONDERE EINFACH - We make the special simple). A distinctive character was therefore denied by the case law for the designation "We make the special simple" for data recording and measuring devices.

However, the mere fact that a designation or statement can also be understood as an advertising slogan does not allow the conclusion that it is therefore devoid of distinctive character (ECJ v. 21.1.2010 - C-398/08 P OHIM/Audi - Vorsprung durch Technik; cf. also ECJ, order of 11.12.2014 - C-253/14 P - BigXtra, para. 36). Thus, advertising slogans can also be protectable as a trademark if they are distinctive. However, longer word sequences are usually not distinctive.

Example Bundesgerichtshof of 1.7.2010 - I ZB 35/09 - The Vision:

The slogan "Die Vision: EINZIGARTIGES ENGAGEMENT IN TRÜFFELPRALINEN" is not distinctive.

The EUIPO has compiled criteria that speak for a distinctive character of slogans.

Distinctiveness of surface patterns as trademarks

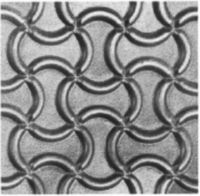

Designs are often denied a lack of distinctiveness and are usually not protectable as a trademark. The ECJ has, for example, denied the Birkenstock sole design trademarkability for clothing and leather goods - ECJ v. 9.11.2016 - Birkenstock Sales GmbH/EUIPO:

On June 27, 2012, Birkenstock Sales GmbH had registered the relief-like surface pattern shown above with the International Bureau of WIPO as an IR trademark, inter alia for leather goods, handbags, clothing and footwear. In the IR registration, it had designated the European Union. The design represents a shoe sole. Birkenstock Sales GmbH had stated that it had been using the design for more than 40 years. On August 29, 2013, the EUIPO rejected the extension of the protection right to the European Union. The reason given was that the design lacked distinctive character (Article 7 (1) of the EU Trade Mark Regulation).

The ECJ dismissed the action insofar as it concerned the goods "leather goods, handbags, clothing and footwear" (ECJ v. 9.11.2016 - Birkenstock Sales GmbH/EUIPO). It thus confirmed the decision of the EUIPO. The ECJ also held that the design merged with the appearance for the goods claimed (clothing, leather goods, handbags, footwear). The sign is presented as a series of regularly repeating elements. Such signs are particularly suitable for surface designs. The goods claimed (clothing, leather goods, handbags, shoes) often have surface patterns. The sign would therefore not be perceived as an "indication of origin" (i.e. as a mark), but as a surface pattern. As a trademark, this design for clothing, leather goods, handbags and shoes is therefore not protectable.

Registration practice of designs as trademarks inconsistent

The application of designs as a trademark is indeed often a legal gamble. The various offices decide differently whether a design is protectable as a trademark or not. This is already evident from the trademark that served as the basic application for the international registration of the Birkenstock sole pattern. It was the German trademark 302012022812, registered for, among other things, leather goods, handbags, clothing and footwear. The sign was absolutely identical to the one that the CFI had denied distinctiveness. The DPMA had thus registered the identical design as a trademark. It thus considered the design suitable to serve as an indication of origin and regarded it as protectable under trademark law. The EUIPO, on the other hand, had denied the design of the Birkenstock sole a trademarkability also explicitly for handbags and bags (ECJ v. 9.11.2016 - Birkenstock Sales GmbH/EUIPO, para. 116 et seq.).

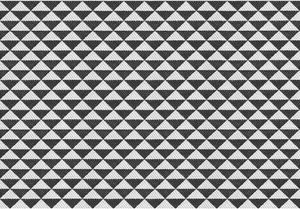

Prada design not protectable as a trademark - EUIPO, decision of 19.12.2023 - R-827/2023-2

A surface pattern by PRADA is also not protectable as a trademark.

The case: On 7 April 2022, PRADA applied to the EUIPO for the above-mentioned surface pattern as a figurative mark for numerous goods, including bags in Class 18 and clothing in Class 25. PRADA did not claim in its application that this pattern had acquired distinctive character due to its high reputation. In its decision of 20.2.2023, the EUIPO largely rejected the trademark application. The sign applied for was nothing more than the external appearance of the goods for which the mark was to be protected. The mark applied for was neither unusual nor otherwise suitable as a distinguishing feature. Triangular designs are widespread.

PRADA filed an appeal against this decision on 18.4.2023. PRADA essentially claimed that the mark was a very specific design mark closely associated with PRADA's iconic protected upside-down isosceles triangle. The pattern creates a very special and very unusual visual effect. The overall impression was therefore distinctive as a mark.

The Board of Appeal rejected PRADA's appeal: for a mark to have distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR, it must be capable of distinguishing the product for which registration is sought as originating from a particular undertaking and thus distinguishing that product from those of other undertakings. This distinctive character was lacking here. In relation to the goods in question, the mark applied for represented a design which is either applied to a part of the goods or is intended to cover the entire surface of the goods and thus corresponds to the external appearance of the goods. The triangular design is a simple and commonplace figurative design as it consists of a regular sequence of triangles of the same size arranged side by side and distinguished by the alternation of different colors. The pattern therefore does not show any significant deviation from the conventional representation of a triangular pattern and corresponds to the traditional form of such a pattern. Such a "banal" pattern is typically used on clothing, textiles or handbags. For this reason, the repetitive pattern will not be perceived as a trademark, but merely as a typical pattern of decorative elements. Due to the lack of the required distinctiveness, the design lacks trademarkability.

Distinctiveness of foreign names

Signs or elements of signs which are devoid of distinctive character in a language of the European Union are not protectable as Union trademarks (Art. 7 II UMV; ECJ v. 20.9.2001 - C-383/99 - Baby-dry).

Signs which the German public does not recognize as descriptive are distinctive and protectable as German trademarks. The German public is familiar with Italian terms frequently used in Germany such as "Monte" (BPatG v. 18.05.2022 - 26 W (pat) 28/17 - MONTES/Vino Monte) or "gusto" (BPatG v. 8.12.2022 - 30 W (pat) 533/21 - GUSTA). It does not know terms that are not typically used in Germany, e.g. "Oro" (cf. LG Hamburg v. 18.7.2018 - 312 O 398/16 - OROCHATA).

Overcoming lack of distinctive character through acquired distinctiveness

Proof of acquired distinctiveness for German trademarks

A lack of distinctiveness as an absolute ground for refusal can only be overcome by proof of reputation (or what corresponds to this for EU trademark law: Proof of acquired distinctiveness).

Signs which are not originally distinctive (Sec. 8 (2) No. 1 MarkenG/Art. 7 (1) b UMV), descriptive indications (Sec. 8 (2) No. 2 MarkenG/Art. 7 (1) c UMV) and designations which have become customary (Sec. 8 (2) No. 3 MarkenG/Art. 7 (1) d UMV) may nevertheless be registered as trademarks if the trademark has become established or has "acquired distinctive character" in the relevant public through the use made of it in relation to the goods or services for which registration is sought . The "acquired distinctiveness" in Art. 7 (3) UMV corresponds to the "acceptance by the public" in Sec. 8 (3) MarkenG (cf. BGH of 21.2.08, para. 26 - I ZB 24/05 - VISAGE, ECJ of 11.03.2003 - C-40/01 - Ansul).

The concept of "use" is the same as for "use preserving the right" according to Art. 15 (1) CTMR/ Sec. 26 (1) Trademark Act (ECJ v. 18.04.2013 - C-12/12 - Stofffähnchen III, para. 30). The case law requires as a basic rule a public awareness of at least 50% (BGH v. 21.2.08 - I ZB 24/05 marginal no. 25 - VISAGE), but in the case of plainly descriptive indications significantly higher (BGH v. 2.4.2009 - I ZB 94/06 (BpatG) Kinder III).

In many cases, this traffic awareness can only be proven by submitting a demoscopic traffic survey (BGH VISAGE loc. cit.). The requirements for this traffic survey are therefore quite high. The traffic survey conducted must indicate the proportion of the relevant public that recognizes the product as originating from a particular company on the basis of the trademark. These circles of the public are first and foremost the end users of the goods applied for. The decisive factor is what the goods applied for are usually used for. For example, if a trademark is applied for "soaps", the traffic survey may not be limited to women, because men also buy and use soaps (BGH VISAGE loc. cit.).

In addition to such a traffic survey, the market share held by the trademark, the intensity, distribution and duration of use of this trademark, the advertising effort of the company for the trademark (in this regard, e.g. BPatG v. 28.11.2012, 29 W (pat) 524/11 - Landlust) as well as statements of chambers of industry and commerce or of other professional associations may also be taken into account (BGH VISAGE loc.cit.). In the case of very well known trademarks, the submission of many court decisions showing that the trademark is very well known may also be sufficient (cf. BpatG v. 21.9.2004, 27 W (pat) 212/02 for three stripes on sports pants as a position mark of adidas AG).

Example of trademarks registered by successful proof of traffic enforcement:

- German color mark 39552630 "Magenta", of Deutsche Telekom AG, among others, for telecommunications services;

- German word mark "POST" for, among other things, the transport and delivery of letters, parcels and small packages.

- Community trademark 003517612 of adidas AG for goods class 25 (clothing, footwear, headwear) as position mark

Proof of distinctiveness for EU trade marks

In the case of EU trade marks, the distinctive character must be present in all member states (cf. (ECJ v. 22.06.2006 - C-25/05 - Storck/HABM). This means that in those parts of the member states where there was no distinctive character (original) from the beginning, there must be a distinctive character (reputation) acquired through use (ECJ v. 25.07.2018 - C-84/17 - Nesté/Mondelez).

However, this does not mean that the applicant or trademark owner can also prove distinctiveness separately for each individual member state. This is because often several linguistic or cultural states are combined in one distribution network (cf. ECJ v. 25.07.2018 - C-84/17 - Nesté/Mondelez). It is therefore sufficient to prove that overall distinctiveness has been acquired in all member states of the Union (ECJ v. 24.05.2012 - C-98/11 - Lindt & Sprüngli v OHIM).

Problems arise if mistakes were made in the registration procedure and protection was granted to a trademark that is in itself not registrable. An example: An EU trademark which is in itself ineligible for protection is registered because the EUIPO has granted it reputation under Art. 7 III CTMR. In fact, however, the trademark owner had not proved at the time of registration that the EU trademark had actually acquired distinctive character in the entire EU. In opposition proceedings before the DPMA arising from such an EU trademark, the opponent must therefore prove that the trademark has also acquired distinctive character through use in Germany. Otherwise, its mark will only be considered weakly distinctive and will accordingly have a low scope of protection, which means that a likelihood of confusion is more likely to be assumed (BGH v. 09.11.2017 - I ZB 45/16 - OXFORD/Oxford Club).

Proof of acquired distinctiveness in the case of German trademarks of use

The acquired distinctiveness also plays a role in the case of trademarks created through use, so-called German "marks of use" according to § 4 No. 2 German Trademark Act (MarkenG).

The relative grounds for refusal in a trademark application

The relative grounds for refusal (Section 9 of the German Trademark Act, Article 8 of the EU Trademark Regulation), on the other hand, are not examined by the offices when a trademark application is filed. Whether a trademark applied for can collide with a trademark already applied for or registered or with another property right (e.g. a company logo) must be examined by the trademark owner himself and an opposition filed or, if necessary, a cancellation initiated.

Trademark application with a disclaimer

Limiting the scope of protection or limiting legal certainty?

A disclaimer in the trademark application excludes the scope of protection of a trademark for certain goods and services in the list of goods and services. However, a disclaimer in the trademark register can only be entered under certain conditions. Restrictions that exclude only certain characteristics of the goods are excluded. This is because it would lead to unacceptable legal uncertainty as to the scope of trademark protection.

Examples of registered and rejected disclaimers

For example, the following disclaimers have been registered in the trademark register so far:

"all the aforementioned services, except in relation to bicycles and related subjects" (DPMA Register No. 30730576).

"except sportswear" (BPatG v. 17.05.11 - 27 W (pat) 536/10

The following disclaimers, for example, have NOT been registered in the trademark register so far:

"excluding goods with a light beige hue" (BPatG v. 15.02.11 - 27 W (pat) 568/10).

"puddings and ice cream excluding those in the shape of a heart" (BPatG v. 08.02.12 - 25 W (pat) 91/09)

Restriction of the scope of protection of a trademark by means of a disclaimer

The limitation of the scope of protection of a trademark by a disclaimer is legally ineffective and cannot limit the scope of protection of a trademark. This is because it would impermissibly exclude in advance the finding of a likelihood of confusion (ECJ v. 12.6.209 - C-705/17 - Patent- och registeringsverket/Mats Hansson).

Example: A disclaimer which, at the request of the Intellectual Property Office, Sweden (Patentoch registreringsverk), excludes an exclusive right to the designation "Roslagspunsch" for alcoholic beverages because the term "Roslags" refers to a region in Sweden and the term "Punsch" is descriptive of one of the goods covered by this registration is without effect for the examination of a likelihood of confusion under trademark law (ECJ loc. cit.).

Repeated trademark applications

The problem of repetition marks

A trademark must be used before expiration of the initial five-year grace period for use. In the case of the German registered trademark, the period begins as soon as no further opposition can be filed against the earlier trademark or the opposition proceedings have ended (Sec. 26 MarkenG). In the case of the EU trademark, the period begins with the registration (Art 18 UMV). After that, a trademark owner risks serious consequences of non-use.

Repeat trademarks

Each trademark application can start a new grace period for use. For trademark owners who have not seriously used their trademark so far, or who never intended to do so because the trademark was only intended to serve as a basis for warnings and claims for damages, the renewed application of the trademark for the same goods or services may be tempting. Now the trademark owner is again spared proof of use for five years. Case law takes a differentiated view of reapplication. If the newly filed trademark is not identical with the older one, e.g. because the younger application concerns a word-figurative trademark whereas previously a pure word trademark was filed, there is no repetition application. The same applies if the geographical area does not match. Therefore, it is not a repeat application if, after filing a German trademark application, an identical sign for identical products is filed as an EU trademark (see BGH v. 24.11.2005 - I ZR 28/05 - GALILEO).

The case law on repeat trademarks

The Federal Patent Court is reticent on the question whether a repeat application is an indication for the ground for cancellation of the trademark application in bad faith (cf.BPatG v. 15.11.2017 - 29 W (pat) 16/14 - YOU & ME). The Court of Justice of the European Union (CFI) has now expressed itself more clearly in the judgment of 21.04.2021, T-663/19 - MONOPLOY. In the case, the game manufacturer Hasbro had applied for the word mark "MONOLOPOLY" over a period of more than 20 years in four trademark applications for partly identical goods and services, including games. A Croatian game manufacturer, which marketed the board game "Drinkopoly", applied to the EUIPO to have the most recent trademark declared invalid. It was said to be a repeat application in bad faith. Other reasons than evading the duty of genuine use were not apparent. The EUIPO had partially declared the trademark invalid, including for games. Hasbro took legal action against this before the ECJ. The ECJ first clarified that not every repeat application is automatically in bad faith. However, it is bad faith to apply for a trademark repeatedly in order to circumvent the proof of use. Therefore, good reasons are needed for a repeat application.

The ECJ therefore asked Hasbro about the motives for the new application. Hasbro claimed that the new application would make it easier for it to administer the trademarks. This did not make sense to the ECJ. After all, multiple trademarks cost more working time and more money. The action was therefore dismissed. The trademark is therefore no longer in force for some of the goods, including games.

Before the application comes the research

Since the offices do not check whether a registered trademark may also be used or would rather lead to a trademark infringement, a trademark search is strongly recommended before filing a trademark application.

This might also interest you:

Received a warning letter in trademark law?

Everything you need to know about a warning letter in trademark law

Trademark opposition

Trademark registration

Trade mark infringement

When is there a trademark infringement of a eu or german trademark and what are the consequences?

Cancellation of a German or an EU trademark at the EUIPO and DPMA

"Distinctive character" in trademark law

What does "distinctive character" in trademark law mean?